- youtube

- bluesky

- Home

- About

- Costume Journal

- Membership

- Conference & Events

- Grants & Awards

- News & Social

In this week's blog, Diego Tamburini, Scientist: Polymers and Organic Materials at the British Museum, shares an insight into ikat textiles. Diego talks us through the dying process, ikats in Central Asia, and his research of these dying techniques during his research fellowship at the National Museum of Asian Art at the Smithsonian Institute, Washington DC, making for a fascinating discovery of these stunningly patterned textiles.

My fascination for ikat textiles started a few years ago when I was awarded a Smithsonian Postdoctoral Fellowship to go and work at the National Museum of Asian Art (Smithsonian Institution) in Washington DC for one year. The project focused on a collection of 76 19th century ikat textiles donated by Dr Guido Goldman between 2004 and 2007. Some of these textiles featured in the exhibition “To Dye For: Ikats from Central Asia” (March 24–July 29, 2018) and they are all described in the catalogue “Ikat: Silks of Central Asia, The Guido Goldman Collection”, edited by Kate Fitz Gibbon and Andrew Hale and published in 1997 by Lawrence King Publishing (London).

Making ikats

Ikat dyeing is a specific type of tie-dyeing. The word ‘ikat’ comes from the Malaysian word mengikat, meaning “to tie”. The idea behind the process is to create the desired pattern directly on the yarns, before weaving. To do so, bundles of threads are marked and repeatedly bound in specific areas with a resist material (usually greased cotton) and then are immersed in a dye bath in order to fix the colour only in the unbound areas left exposed.

The process is very difficult and time-consuming, as it is repeated for each different colour. The weaving is carefully carried out at the end of the process, after stretching the dyed threads on a loom in the correct order.

As the colour in the dye bath tends to bleed under the resist material and due to the slight movement of threads caused by the strains imposed by the weaving process, ikat patterns show a characteristic “blurriness” or “feather-like” effect. Interestingly, the practice seems to have developed independently in different continents, such as Asia, Africa and South America, leaving scholars to debate whether a common origin of ikat dyeing exists among the various traditions.

Ikats in Central Asia

Central Asians ikats, while bearing technical similarities to other ikat traditions, are generally characterised by their bold and large abstract patterns, sometimes made up of up to eight different colours. The word abr from the Persian word for ‘cloud’ is the term used to refer to ikat in Central Asia and the term abrbandi to the ikat weaving technique. As the desired pattern had to be planned in advance, several craftsmen, including thread binders, dyers and weavers worked together to achieve the final result. 19th century ikat fabrics could be made of silk and cotton or entirely of silk (shohi), mostly in plain or satin weave. Shohi fabrics had an iridescent finish and made a rustling sound when worn, adding to their appeal. Discerning buyers often checked the sound of the fabric in addition to its patterns and colour combinations before finalising their purchases. Something they still do today…

The ikats in the Goldman collection are all from Central Asia, and Goldman’s intention was to only buy traditionally-made and relatively old ikats. However, tracing the exact production date and provenance of textiles in museum collections is very difficult. Goldman’s ikats were all attributed to the 19th century, supposedly spanning from the beginning to the end of the century, mostly based on stylistic interpretation. While for most, the geographical provenance was Uzbekistan, some were more precisely related to Bukhara, Samarkand or the Ferghana (or Fergana) valley straddling the border between Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. In fact, ikat production in the 19th century was centred predominantly around these regions. During the Soviet period (1924-1991), while the production of elaborately patterned time-consuming ikats declined, cheap printed fabrics with ikat patterns became popular. Elaborate ikat fabrics have, however, seen a revival in the last two decades since independence following the fall of the Soviet Union, with ikat being perceived as the national fabric of Uzbekistan. Ikat fabrics could be used for entire garments or to edge or line garments made of plain, striped or brocaded textiles creating bright and colourful contrasts. Often several garments were worn simultaneously, layered, the colour combinations of each chosen to achieve maximum striking effect.

Studying the dyes

The main idea behind this project was to exploit the information hidden in the dyes to possibly refine the provenance and dating of these textiles. In fact, dyes do not only inform on the manufacturing materials of a textile, but some dyes can be linked to specific geographical areas or time periods. The information is even more precise for synthetic dyes, as their first synthesis is often documented. Therefore, the detection of synthetic dyes can be used as a dating tool.

Despite all the good intentions, I arrived in Washington DC in February 2020, so you can imagine how this story continues... After about four weeks, during which I barely managed to settle, I was asked to work from home like most people during the initial phase of the Covid-19 pandemic. I thought that was the end of my project and experience, but fortunately some analyses on the Goldman ikats had already been done and I was able to work on previously acquired data and focus on the interpretation of the results. The analyses of about 100 samples from 26 ikats had been performed with an analytical technique called high pressure liquid chromatography coupled to diode array detector and mass spectrometry (HPLC-DAD-MS), which briefly enables all the molecules in a dye mixture to be separated and identified singularly. This enabled the identification of most sources of natural dyes used to produce the textiles. For red, cochineal, madder and lac dye; for yellow, larkspur, pagoda tree flower buds and grape vine leaves; for blue, indigo. Tannins were also used to adjust the shade of the red colours. These dyes were traditionally used in Central Asia, confirming the geographical provenance of these textiles. Additionally, 9 of the 26 textiles were found to contain synthetic dyes, such as fuchsine, methyl violet, malachite green and rhodamine B, which were synthesised in 1856, 1861, 1877 and 1887 respectively. This information allowed me to adjust the dating of these 9 textiles, mostly to a later period compared to the stylistic interpretation. The results of the investigation were published in the international open-access peer-reviewed scientific journal Heritage Science.

Ongoing research

Although my fellowship was successful, there was a very sad side of the story for me... I never saw the textiles in person. I only saw images on a computer screen. This was one of the reasons why I kept pursuing this research line. In mid-2021 I came back to work at the British Museum, and it did not take me long before checking Collection Online and see that some 19th century Central Asian ikats are indeed part of the collection. I also noticed that some of the patterns are extremely similar to what I had seen on some of the Goldman ikats.

With the support of Zeina Klink-Hoppe (Project Curator for the Modern Middle East at the British Museum) I took some tiny samples from six of the BM’s ikats to compare with the results obtained from the National Museum of Asian Art’s textiles. I had finally managed to spend a full day with these magnificent textiles.

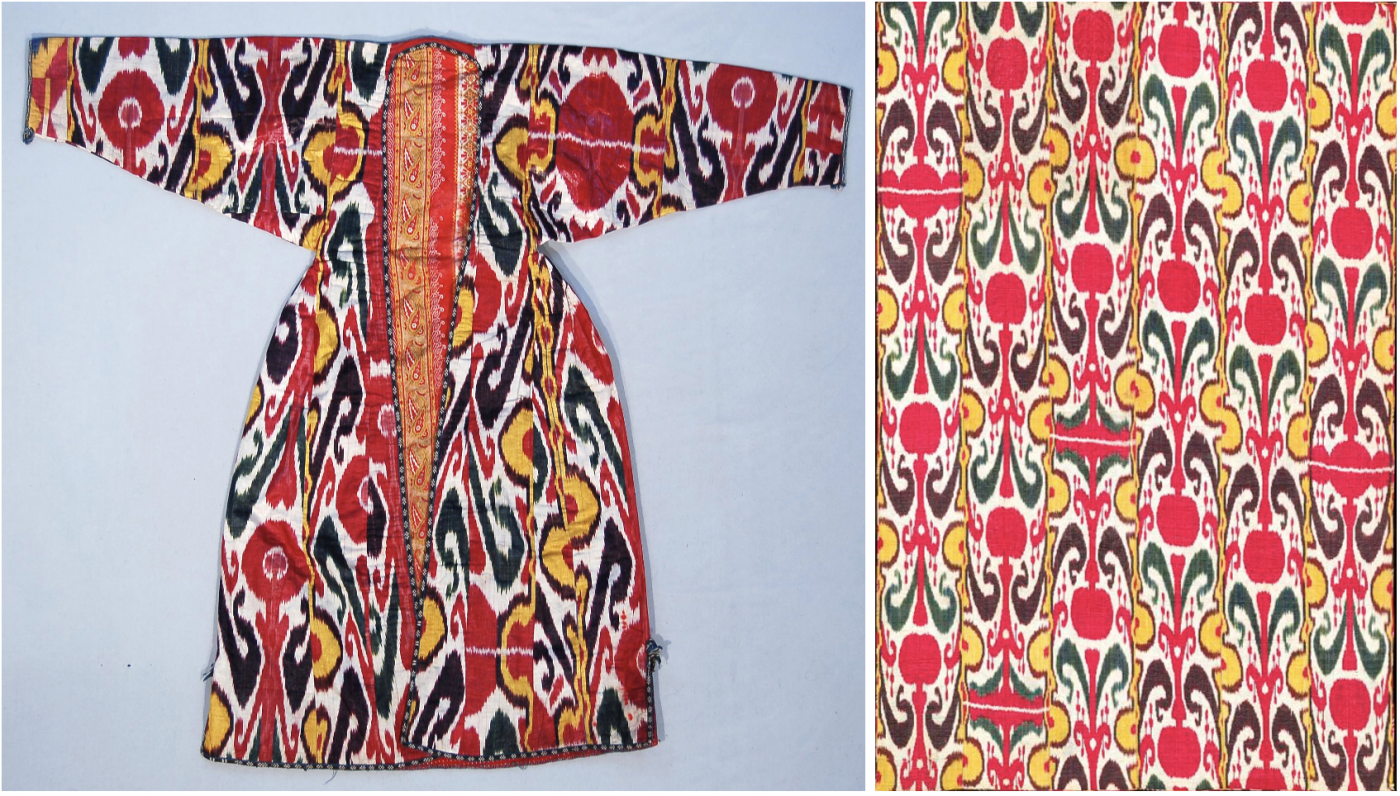

The textiles are five robes or coats (As1994,04.2; As1956,07.38; 2014,6013.1; 2014,6013.2) and a quilt (As1993,27.6). Having them out on the table was a feast for the eyes.

I walked away with several samples that I will soon analyse together with some additional samples from the Goldman’s collection. I hope to share some interesting results soon about possible connections between these textiles and expand our knowledge on the dyes used to create their vibrant colours.

Diego Tamburini is an analytical chemist by training and obtained his PhD in Chemistry and Materials Science from the University of Pisa in 2015. He specialised in the use of chromatographic and mass spectrometric techniques for the characterisation of organic materials. He joined the Department of Scientific Research of the British Museum in 2016 with an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship focusing on the application of liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry to the identification of natural dyes in historical and archaeological textiles. In 2020, he moved to the Department of Conservation and Scientific Research of the National Museum of Asian Art (Smithsonian Institution) as a Smithsonian Postdoctoral Fellow with a project focused on the dye analysis of the ikat textiles present in the Guido Goldman collection. He joined the British Museum again in 2021 in the role of Scientist: Polymers and Modern Organic Materials. His current interests and research lines are related to the development of new analytical strategies based on gas and liquid chromatography coupled with high resolution and high accuracy mass spectrometry to unlock new ways of characterising and identifying natural and synthetic organic materials.

If Diego's research has ignited your ikat interests, examples can be seen on display in the British Museum; take to the Islamic Gallery's Central Asia case to see a hair-cover and coat-lining both made from silk ikat cloth, and to the Japan Gallery to see a banana tree fibre cloth with ikat decoration.

For those who cannot make it to the museum in person, the museum's online collections database has a wealth of fascinating pieces to explore.

To read about dress history research projects, revisit our past blog posts.

Image gallery

Markings on thread bundles in readiness for binding. Margilan, Ferghana Valley. © Zeina Klink-Hoppe

Loom at the Yodgorlik silk factory set up for weaving ikat. Margilan, Ferghana Valley. © Zeina Klink-Hoppe

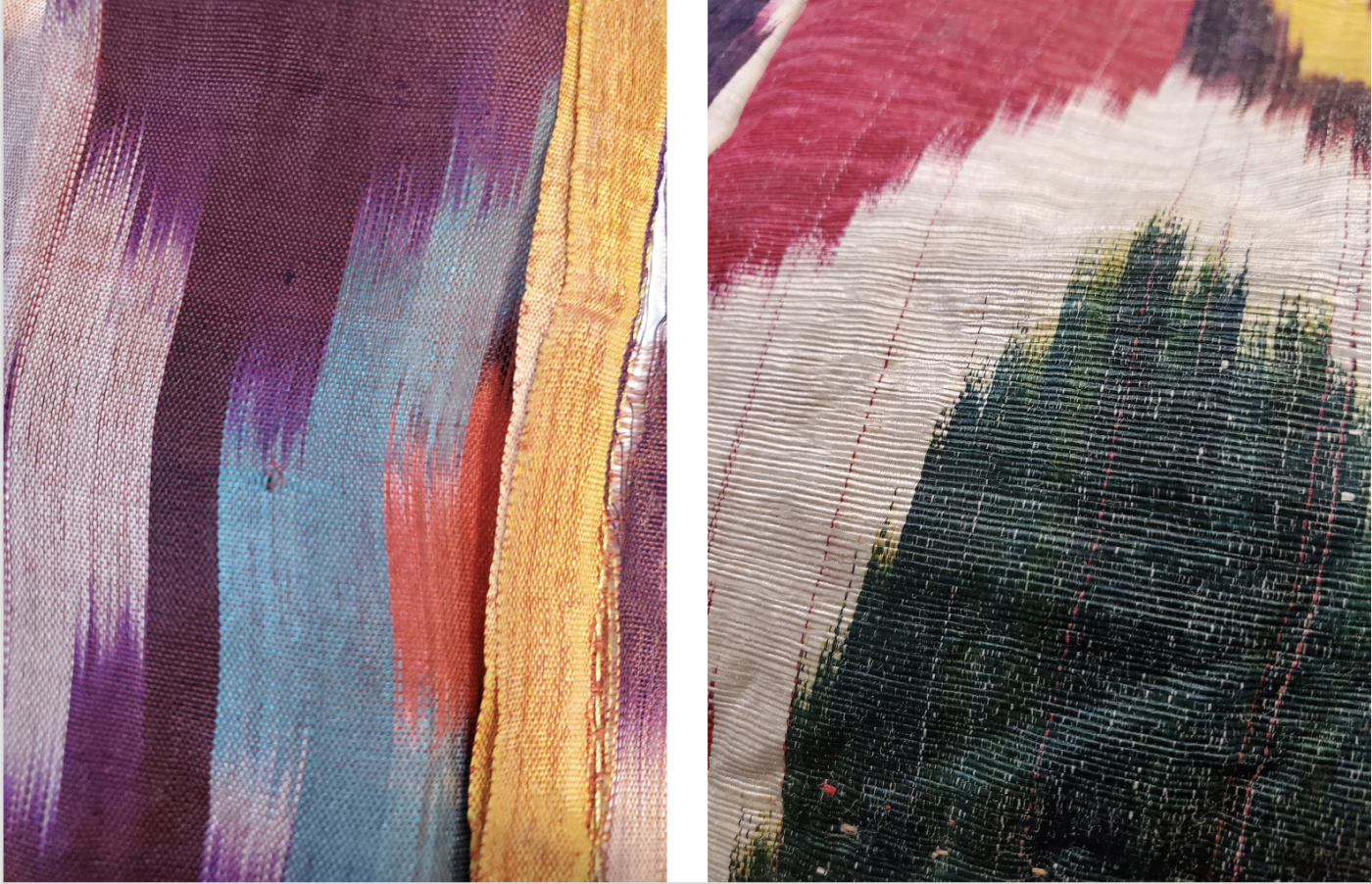

Details of ikat patterns showing the typical blurriness effect. © The Trustees of The British Museum.

Ikat fabrics for sale in Bukhara. © Zeina Klink-Hoppe

As1994,04.2 from the British Museum (© The Trustees of the British Museum) and from the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, DC.S2004.74 from the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, DC.

2014,6013.2 from the British Museum (© The Trustees of the British Museum) and from the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, DC.S2004.84 from the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, DC.

The six ikat textiles at the BM’s textile storage at Blythe House during the sampling campaign. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Photo of Diego Tamburini during sampling. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Photo of Diego Tamburini during sampling. © The Trustees of the British Museum