- youtube

- bluesky

- Home

- About

- Costume Journal

- Membership

- Conference & Events

- Grants & Awards

- News & Social

In this week’s blog, News Editor Babette Radclyffe-Thomas reviews the British Museum’s groundbreaking exhibition China’s hidden century.

China’s hidden century is a pioneering exhibition showcasing 19th century China material culture at the British Museum and fashion, dress and costume are at its heart. Conservation of key items form the centrepiece of this exhibition which showcases items that have never been placed on public display before.

A result of a four-year long AHRC funded research project, the exhibition sees the unprecedented collaboration of over 100 scholars from 14 countries. Over 300 objects are on display; half from the British Museum, half borrowed from 30 different British and international lenders, with most being publicly displayed for the first time.

In this exhibition, the 19th century in China stretches from the accession in 1796 of the fifth emperor of the Qing dynasty, Jiaqing, to the abdication in 1912 of the tenth, Puyi. Spread across seven rooms, the exhibition’s initial room focuses on imperial robes and costumes for court, then the following room focuses on military wear including uniforms from the Taiping Rebellion (1850 to 1864). The following rooms focus on art, everyday life, the global Qing and the exhibition culminates on reform to revolution.

The curators’ aim of the exhibition is to humanise a century dismissed globally as a period of China’s decline. During this era, Chinese society was extremely tumultuous, with civil and foreign wars (such as the Opium Wars), ending with a revolution that ended 2,000 years of dynastic rule. During this time, the creativity of material culture persisted.

Wenyuan Xin, Project Curator China’s Hidden Century at the British Museum, says: “I have relished the opportunity to explore and tell the story of an often-underestimated period of Chinese art and culture. Over the course of just over 100 years China transformed from a dynastic empire to a modern republican nation. Through this exhibition, we hope to communicate the drama, complexity and conflict of this process.”

Jessica Harrison-Hall, Head of the China Section, Curator of the Sir Percival David Collection, Chinese Ceramics and Decorative Arts at the British Museum, comments: “In this show we have sought to highlight the creativity and resilience demonstrated by so many citizens of Qing China amid exceptionally hard times. Our aim was to celebrate the contributions of remarkable individuals. Putting the show together has been a huge collaborative effort and it has been wonderful and inspiring to work with so many scholars, collectors, designers and students.”

The exhibition displays a wide array of costumes including high status imperial garments. Empress Dowager Cixi’s robe features a large, swooping phoenix amid lush chrysanthemums and wide sleeve bands demonstrating a creative combination of Manchu, Chinese and Japanese motifs, in purple, gold and turquoise. The exhibition also contains a pair of embroidered bound feet lotus shoes, military and childrenswear. A pair of brightly coloured 19th century children’s clothes with a matching pair of tiny boots is a particular highlight.

It is the humble, functional clothing that provides a fascinating insight into everyday garments such as a straw cape used by farmers and workers that was painstakingly restored by conservators. “Perhaps the most challenging item was a striking rain cape made from the leaves of the Chinese windmill palm (Trachycarpus fortunuei). Constructed with the long, narrow leaves of the palm arranged in densely overlapping rows, folded over and stitched together, water would have readily run off its surface rather like a thatched roof. The cape would likely have been worn by rickshaw pullers, street cleaners or labourers, often together with a wide brimmed hat, to protect themselves from the rain. Surviving examples of everyday work wear like this are relatively rare.” Monique Pullan and Misa Tamura, Organic Materials Conservation Section, Collection Care note in their extensive blog piece detailing the conservation process of this specific item.

China’s hidden century also details the role of imperialism, and interestingly displays pieces of art or photos next to the garments to bring the clothing to life. Several rooms feature hanging speakers that play recordings of texts originally composed in the Qing era while voiceovers and projections onto screens create an engaging and immersive experience. The exhibition lighting is dim, ensuring focus on the items on show.

Additionally, the role of women and feminism is central to the exhibition, as shown in the decision to feature Chinese revolutionary, writer and feminist Qiu Jin in the final room to close the exhibition.

Since the exhibition has opened, it has come to light that the curatorial team included translations by translator Yilin Wang of Qiu Jin’s poetry without acknowledgement. Wang raises the issue of copyright infringement and notes that this is particularly pertinent due to the extensive work involved in translation. “When I’m translating, I am using my knowledge of poetry in English, I’m using my knowledge of classical Chinese literature, I’m doing background research on the poet and … on the time period that Qiu Jin was writing in. I am also often going through 10 to 15 drafts of the same poem to find the right words, the right expression, the most eloquent way of translating idioms and allusions, the right way to capture the spirit and emotional power of the poetry rather than a word-by-word translation” Wang shares.

This has led to a public statement from the British Museum’s curatorial team attributing the inclusion of Wang’s work to an “unintentional human error” and the subsequent removal of these translations from the exhibition. “It’s really important to have discussions about copyright, about crediting translators’ labor, about making sure that this does not happen again and taking steps to correct it properly,” Wang shares.

The Citi exhibition China’s hidden century runs from 18 May 2023 to 8 October 2023 in the Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery at the British Museum and a programme of events runs throughout the exhibition period.

The costume society regularly reviews textiles related exhibitions, click here to explore our blog. Click here to become a member today!

Image gallery

Elaborate headdress, 1800-1900, China. © The Teresa Coleman Collection.

Empress Dowager Cixi’s robe, China, about 1880–1908. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Jacket with border of steam ships 1860-1900 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Snuff-bottle with image of Li Hongzhang (1823–1901), Bejing, 1900-1910. © Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection. Photographed by Nick Moss.

Unidentified artist, Ancestor portrait of a bannerman. With permission of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. © ROM.

Unidentified artist, Portrait of Lady Li (Lu Xifu's Wife). Ink and colour on paper, China, about 1876. Gift of Mr. Harp Ming Luk. With permission of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. © ROM.

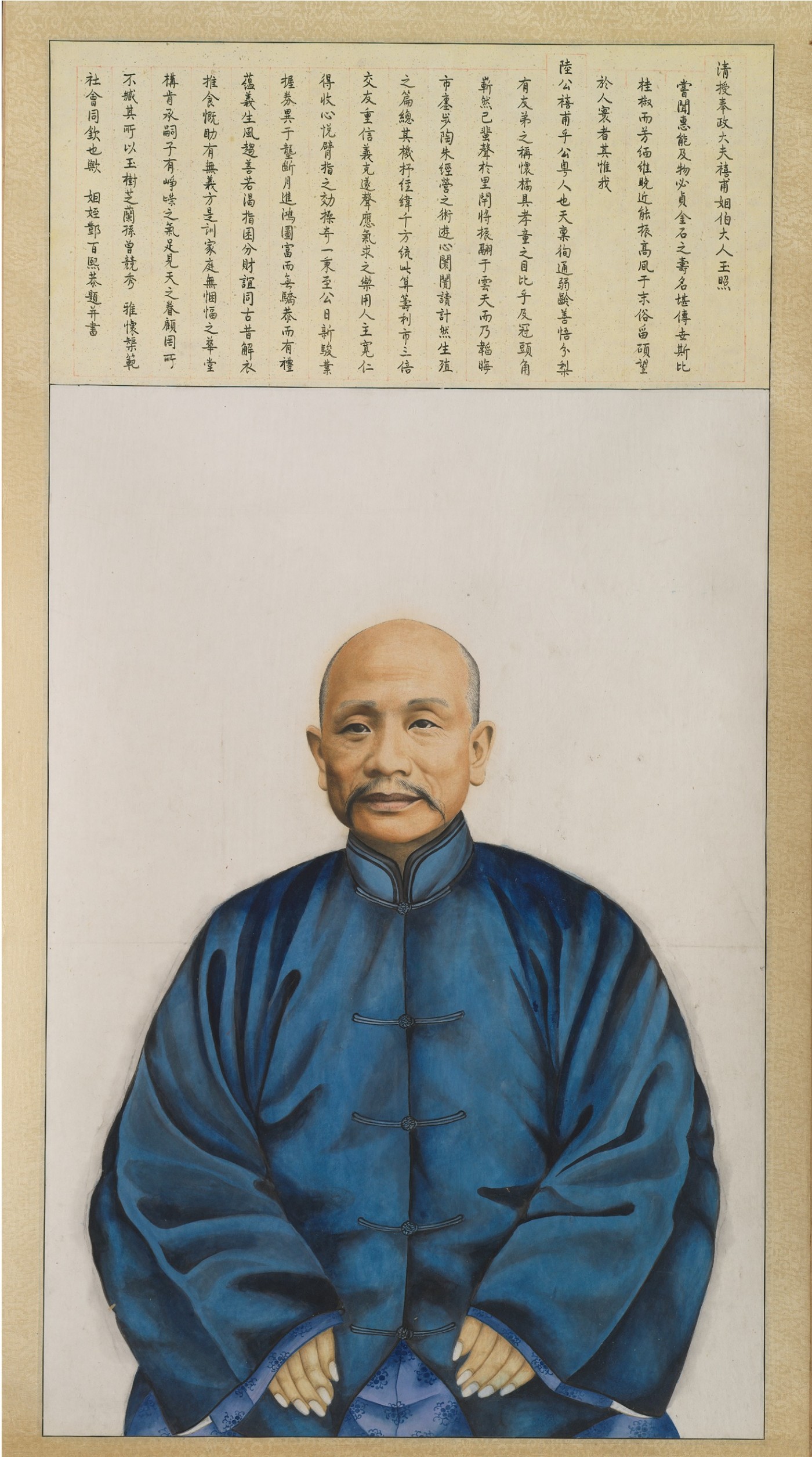

Unidentified artist, Portrait of Lu Xifu. Ink and colour on paper, China, about 1876. Gift of Mr. Harp Ming Luk. With permission of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. © ROM.

Waterproofs for a worker, 1800-6, Southern China. © Trustees of the British Museum 2023.