- youtube

- bluesky

- Home

- About

- Costume Journal

- Membership

- Conference & Events

- Grants & Awards

- News & Social

Officers, gentlemen, and dedicated followers of fashion... author and lecturer Dr Amy Miller explains how the history of Royal Navy clothing isn't as 'uniform' as it first appears.

Today uniform is a recognisable element of service life – it is widely standardised and its wearers instantly identifiable. But standard dress for the Navy was in fact introduced comparatively recently, in the mid-1700s, and initially only as a way of distinguishing rank for officers.

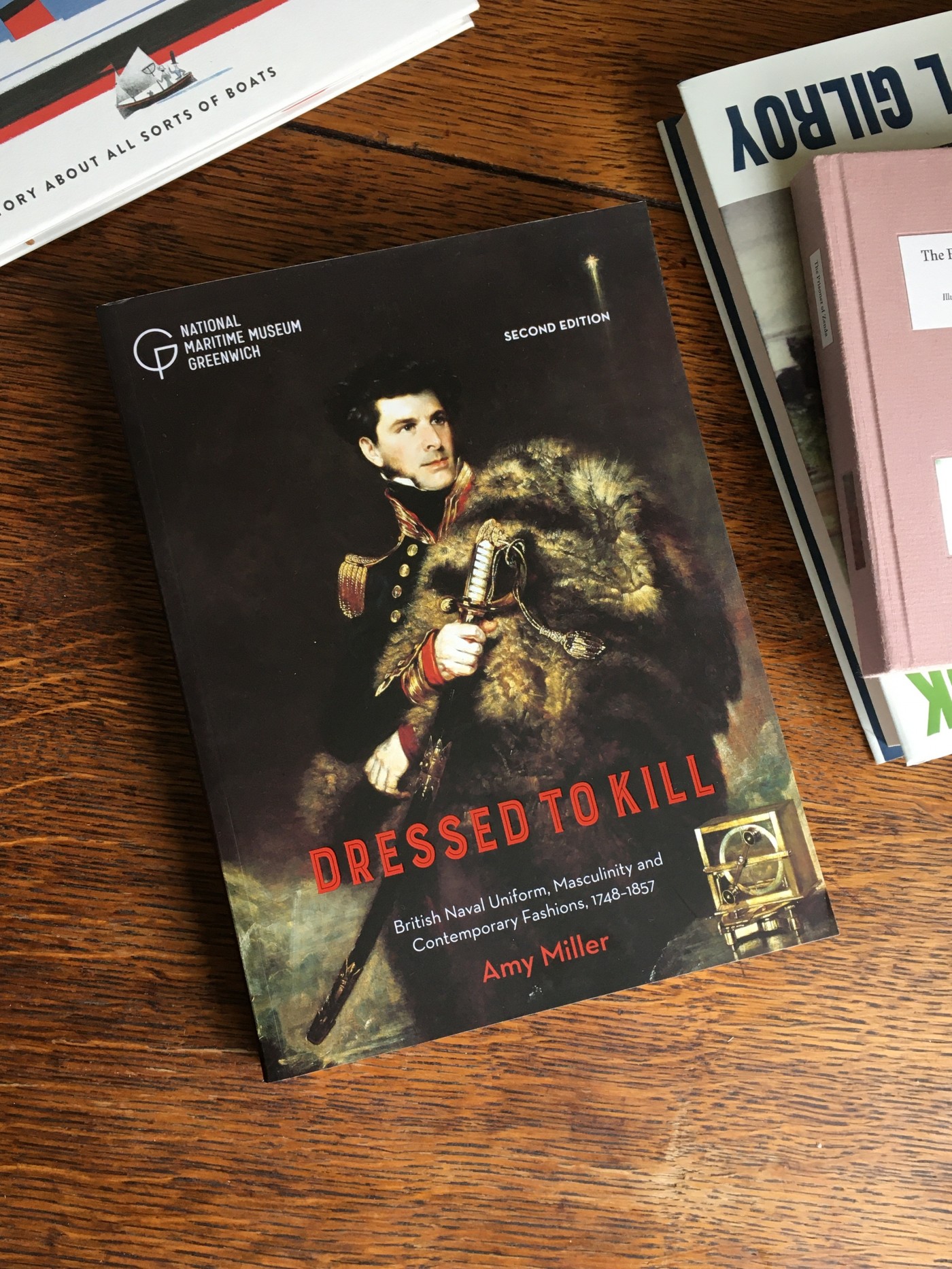

In a revised and updated edition of her book Dressed to Kill, Dr Amy Miller – author, lecturer and former curator at Royal Museums Greenwich – explores the concepts of identity, fashion and masculinity through uniform, and considers the regulation of dress as a reflection of developments in wider society.

Here, she examines some of the pieces that are featured in the publication from the National Maritime Museum’s extensive naval uniform collection.

Uniform, first introduced by the Admiralty in 1748, was regulated dress, but it was supplied at the officer’s expense and not issued by the Navy.

While the regulations were stipulated and issued by the Admiralty in the form of patterns, the garments were created by the naval officers’ own tailors, often in collaboration with their clients.

This gave officers some scope to personalise uniform and to express their desire to keep up with the latest fashions. Many of these tweaks are seen in the details of naval uniform, which reveal small embellishments that speak to the preferences of the men that wore these clothes and give us small clues about their lives.

Captain Alexander Hood (1758–98) was first cousin to Samuel Hood, First Viscount Hood (1724–1816), and Alexander Hood, First Viscount Bridport (1726–1814), both of whom became Admirals in the Royal Navy.

He served on James Cook’s second voyage (1772–75) and later took part in the Battle of the Saintes. By 1790 he was in command of the frigate Hebe, but he suffered subsequently from ill-health and it was not until the end of the decade that he returned to active service. He died from a wound to his thigh in April 1798, at the end of a close-fought battle with the French ship Hercule in the Channel.

Details from his full dress uniform show us that he had a taste for luxury – the wool that he chose for his uniform was of a high quality and the collar was lined not with more wool, but with white velvet. In addition to his taste for fine fabrics, he was also wary of pick-pockets. When we lift his pocket flap, the pocket itself is secured with an additional button to ward off any would-be thieves.

As these clothes are tailored (cut and sewn to the body of wearer) instead of ready-made (cut to a set of general measurements), we can learn a bit about Hood himself.

We know that one shoulder was slightly higher than the other, his arms were unusually long and his rib-cage over-large as well. A good tailor could generally conceal any physical anomalies. Some of these aspects of Hood’s body, however, are indicative of any number of conditions that might have been the source of his ill-health.

James Black (died 1868), who only saw very brief active service, was appointed surgeon in the Royal Navy in September 1810 and served until sometime before December 1815. By 1824, it was noted in the ‘Navy List’, a record of officers who served in the Navy, that he was a medical doctor.

Before his eventual retirement from the Navy in 1839, despite not being on active service, he clearly still wore the uniform. His full dress coat, an 1825 pattern, features the badge of a snake twined around an anchor on the collar and the same device is repeated on his buttons, indicating his rank as a medical officer. The collar’s interior features a very delicate, hand-stitched Vitruvian scroll – an expense that would only have been visible to very few people.

While we have been looking at the hidden embellishments indulged in by Naval officers, there are also objects with hidden messages that related to quite public events.

A cocked hat presented to Admiral Charles Napier (1786–1869) bears an inscription stamped on its silk lining: ‘Presented To Admiral Sir C. Napier By The Workpeople In the Employ of Messr’s Christys’, Bermondsey Street, Southwark November 9, 1855’.

The band is also embroidered with fouled anchors and a ‘guilloche’ pattern (intricately intertwined stitching).

This hat was a presentation piece in acknowledgement of Napier’s successful election to parliament.

Napier’s career was not without controversy. His period of command during the Crimean War, and the failures of the campaign, led to an acrimonious relationship between himself and the Admiralty, which dogged his early political career.

The influence of fashion on early naval uniform is clear in the choices of embellishment and detail, although it was not without criticism at the time, particularly when it came to the incorporation of French styles into regulation clothing.

The relationship between uniform and societal fashions is something that remains to this day.

Although the Admiralty intended uniform to codify rank and status, independent of trends, regulated dress instead became a reflection of social change and drove fashions as much as it took its cues from them.

This blog post first appeared on the Royal Museums Greenwich and is shared with consent.

For a chance to win a copy of Dressed to Kill simply follow the Costume Society on Instagram and/or Twitter and comment on our book giveaway post telling us why you would like to receive a copy of Dressed to Kill. The giveaway goes live on Monday 21st February and closes on Monday 28th February 2022 23:00 UK time.

In addition, Costume Society members enjoy 20% off Dressed to Kill from the Royal Museums Greenwich website - check your email for the discount code. Offer ends 20th March 2022.

Image gallery

Dressed to Kill by Dr Amy Miller.

Detail of Royal Naval uniform: pattern 1825-32. Belonged to Surgeon James Black.

Hat belonging to Admiral Charles Napier.