- youtube

- bluesky

- Home

- About

- Costume Journal

- Membership

- Conference & Events

- Grants & Awards

- News & Social

In this week’s blog, Costume Society Ambassador, Martha Strachan, reviews Tate Modern’s ‘Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope’ exhibition. Exploring the pioneering Polish artist’s, Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017), most radical work, the exhibition features monumental fine art textile installations, called Abakans.

I see fibre as the basic element constructing the organic world on our planet, as the greatest mystery of our environment. It is from fibre that all the living organisms are built, the tissue of plants, leaves and ourselves.

-Magdalena Abakanowicz

Guts and gashes, holes and wounds, contemplation and stillness, floating and breathing, weaving and stitching. Wondering around the huge textile sculptures at the Magdalena Abakanowicz exhibition is a truly immersive experience, the textures, colours, and forms all evoking a myriad of feelings and thoughts.

The exhibition ‘Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope’, at the Tate Modern, is extremely emotive, whether it be feeling of awe at the sheer scale of her work, contemplation due to the dark history her artwork reflects or inspiration due to Abakanowicz's extraordinary technical skill.

The intimately curated exhibition follows the Polish artist, Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017), through her development as a pioneering textile artist. From punch cards for weaving, to abstract tapestries, the exhibition grows to become huge installations of the artist most ground-breaking work, her ‘Abakans’ (1960s-70s). Made from sisal, wool, and hessian the 26 ‘Abakans’ are huge organ-like woven sculptures displayed hanging closely to one another, as the artist had intended. Inviting you to walk around and observe the intimate details the forms hide and reveal.

One of Poland’s most internationally acclaimed artists, Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017) is a sculptor and fibre artist. Abakanowicz was born into an aristocratic family in Falenty, where she grew up in the countryside. However, come the Second World War followed by the communist regime, her family's circumstances became grave. Abakanowicz witnessed atrocities from a young age. The artist’s personal experiences are fundamental in understanding her artwork, she took inspiration from polish folklore and the ‘enchanted forest’ she lived in as a child, whilst also navigated her trauma through her artwork. The exhibition includes a timeline in the final room however I’d encourage you to read about her upbringing before visiting.

In 1954 she graduated from the Academy of Fine Art, Warsaw, having studied painting and weaving. In 1962 she exhibited at the first International Tapestry Biennial in Lausanne, and a few years later, in 1965, won the Gold Medal in Applied Arts at the São Paulo Biennia. Her recognised international success saw Abakanowicz appointed as a professor at the Poznańart Academy until 1990. In 2020 it was renamed the Magdalena Abakanowicz University of Arts.

The exhibition starts off following the artist’s progress and ideas. Therefore, the first two rooms feature more two-dimensional work from the early 1960s. A highlight in the first room is a small collaged plan of a tapestry displayed alongside the final tapestry itself. Though the collaged plan may be multi-layered, and the tapestry is two dimensional, the lines and form of the collage translate so that the viewer still witnesses a complex abstracted and multi-layered composition in the final outcome, a taste of what’s the artist’s work will develop into.

The following room shows Abakanowicz beginning to explore more three-dimensional pieces in the 1970s. This rooms features large circular textured tapestries that have been woven to appear weathered and torn. In this gallery is a key piece called ‘hand’, 1975. Easy to miss due to its small size, it’s an important piece in understanding more about the artist. Made from sisal a single hand lays in a small display case. This piece introduces a running theme in her work, the fragmented body. A reaction to the barbaric scenes she witnessed in World War two. This work, alongside the piece next to it, head, 1976, if the first piece you begin to view rope and sisal, hardy industrial textiles, as body parts. It’s extraordinary how Abakanowicz could make something solid, dry and tough seem fluid and alive.

The next room is where Abakanowicz work starts to grow both conceptually and in scale. At the very beginning of this room is a tapestry, that while still on a wall and not as huge as her Abakans, is a fascinating example of the female body in her work. Named ‘pregnant’, c. 1970-80, the tapestry has a brown-red swelling centre with a slit down the middle. The piece plays on themes of fertility and womanhood, a theme that flows throughout her exhibition. The ominous charred border and gash in the centre evokes feeling of pain, devastation, and violence. I felt as though the whole exhibition was like a memorial to the artists memories of her childhood destroyed by war and communist Russia, whilst also questioning themes of fertility, womanhood and objectification.

“The Abakans were a kind of bridge between me and the outside world. I could surround myself with them; I could create an atmosphere in which I somehow felt safe because they were my world; they were something between figurative and natural, like animals, like figures, while abstract, like geometric forms, but never to be definitively described. They were terribly important not only for me but because they are different from everything.”

- Magdalena Abakanowicz

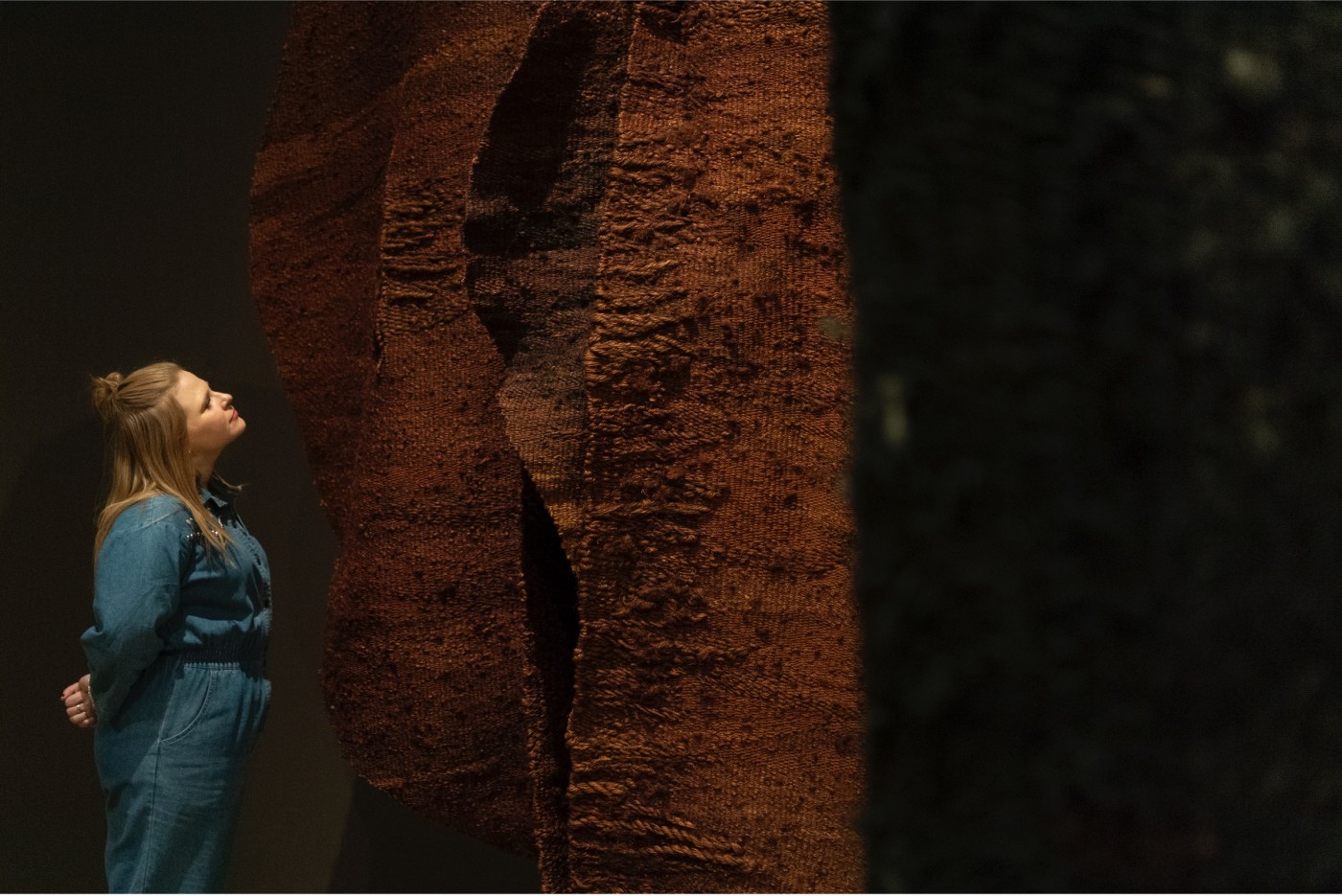

In the next large room are the stars of the show, the ‘Abakan’s’. Magdalena Abakanowicz rejected the negative and gendered connotations historically associated with textiles. She wished her art to break-away from the traditional tapestries seen in history. Her Abakans, deriving from her surname, astounded critics when she first started to make the forms in the 1960s. Some measuring up to five meters tall and made from woven fibres such as sisal, the 26 Abakans in the exhibition are huge ambiguous and organic soft-form sculptures that come together to make a forest-like installation.

Being hung from the ceiling meant the huge Abakans sway very slightly, creating a dynamic quality to these bodily pieces. Though their epic size makes you feel small, as if they could envelope you at any moment, their many details create a sense of intimacy; from the cascading sisal hanging like locks of hair to the ropes knotted resembling entrails to the textured weaving that grows like veins.

There is something so human about the Abakan’s, the gashes, veins and lacerations create a visceral sense of body, evoking feeling of pain and empathy. However, they also remind the viewer of clothing. Many Abakan’s had shoulder-like features, functional for holding the structure and weight of the piece, however alongside the various flaps, seemed reminiscent of a garment of clothing. This creates a sense of objectification, adding to the intimate, slightly uneasy atmosphere of the installation.

The colours of the Abakans in the show appear to evolve. To start with they’re bloody and muddy in tones; browns, burgundies, and ochres. However, in the latter end of the installation the Abakans shift to vivid oranges, reds and yellows. With black Abakan’s in places too; appearing charred and sombre. As with all aspects of the exhibition the colour palette is multifaceted, poignant and expressive, adding to the sense these sculptures are very much alive.

If the fine art concepts, forms, and compositions aren’t impressive enough, the artists staggering technical ability will have you wondering how she even made her pieces. She turns the traditional warp in all directions, even sideways and she weaves in a variety of materials, tensions, and densities.

Textiles can often be associated with soft and fine textures. Though Abakanowicz used hardy, industrial, and abrasive textile materials like horsehair, gauze, burlap sacks and sisal rope, often scavenging whatever she could find. These materials are painful to use, and as a maker myself, a part of me winced as I observed these hardy textiles fibres, thinking of the scratches and calluses the artist would have obtained making her work. Only adding to the visceral feeling of pain in her installations.

Being a fine art textiles exhibition, something you don’t see so much of at the Tate Modern, did have me coming back to the same thought throughout the exhibit; How does textiles interact with a viewer in a white cube gallery setting? Textiles, at its core, is tactile, and in non-gallery scenarios, whether you’re a maker or simply a person that wears clothes, you want to run your hands through fibres and clench surfaces to experience the textile fully. There is even a video of Abakanowicz herself tactilely touching her Abakans in the exhibition. Though of course the relationship an artist has with her art will always be more intimate than that of the viewer, it raises the question, do you fully experience textile art in a fine art setting where you are distanced from the piece? While the preservation of these extraordinary pieces is crucial, and you absolutely should never touch art in a gallery, you can’t help but feel by taking away an integral sense, touch, the meaning of the installation is dulled. With that said, I was grateful that there was no physical divider between the viewer and the Abkhan installation, so that one’s eyes could absorb as much of the textures as possible.

As you come from the extraordinary Abakans, the final room has a simpler approach about it. This room features a timeline of the artists life and images of her outdoor installations, that she developed in the 1970s, as well as one large wood and metal sculpture. Though slightly less eye-catching a room, it shows her breadth of work and reiterated Magdalena Abakanowicz significance and impact she had on the contemporary art world of Poland, and indeed the world.

A clever feature of the exhibition is occasional window slits in the gallery walls, giving a glimpse into the next rooms showing the next colours and forms to come. As well as being visually striking, this weaves the exhibition together, and emphasises the artists development.

‘Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope’ demonstrated how pioneering Abakanowicz was as a fine artist, it’s an intimate exhibition that sees the artist’s journey through art, despite and because of her memories. Offering a rare opportunity to experience Abakanowicz Abakan installations, the exhibition sees extraordinary details, raw materials, shifting colours and growing forms.

Be warned, give yourself plenty of time if you’re a textiles lover and texture fiend, the sheer scale of Abakanowicz works alongside the many details that her pieces reveal, means you could stare at one piece for hours.

Magdalena Abakanowicz was curated by Ann Coxon, Mary Jane Jacob, and Dina Akhmadeeva. The exhibition is organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with the Fondation Toms Pauli at the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne and Henie Onstad Art Centre, Høvikodden.

The exhibition is on until the 21st of May 2023, and is open daily 10.00 – 18.00. The exhibition cost £16 for non-member. Members go free. Age 16 to 25? Join the Tate's Youth Collective for £5 tickets and more.

The Costume Society regularly review exhibitions, click here to take a look at the blog post on Gianni Versace Retrospective opens at Groninger Museum. Make sure to follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter to keep up-to-date with The Costume Society blog, events and news. Become a membere here!

Image gallery

Magdalena Abakanowicz at her loom, 1966. © Estate of Marek Holzman

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Helena 1964–5, Marlborough Gallery, New York, © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Tapisserie 21 brune 1963, Brown Textile 21 (Tkanina 21 brązowa), Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego , © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw.

Magdalena Abakanowicz’s work at Tate Modern. © Tate Photography, Madeline Buddo.

Magdalena Abakanowicz’s work at Tate Modern. © Tate Photography, Madeline Buddo.

Observe the many details of Magdalena Abakanowicz’s work at Tate Modern. © Tate Photography, Madeline Buddo.

Magdalena Abakanowicz’s work at Tate Modern. © Tate Photography, Madeline Buddo.

Abakan Orange, 1968 by Magdalena Abakanowicz. © Tate Photography, Madeline Buddo.

Abakan January-February, 1972 by Magdalena Abakanowicz. © Tate Photography, Madeline Buddo.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Abakan Yellow 1970, National Museum, © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Abakan Situation Variable 1971, Art collection of the city of Biel-Bienne, Switzerland, © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw.

Magdalena Abakanowicz Abakan vert 1967–8 Private collection, Warsaw