- youtube

- bluesky

- Home

- About

- Costume Journal

- Membership

- Conference & Events

- Grants & Awards

- News & Social

In this week's blog, Costume Society member and Keeper of Costume, The Olive Matthews Collection at Chertsey Museum, Grace Evans gives us a peek behind the scenes at Blooming Marvellous: Flowers in Fashion.

Amongst our many activities at Chertsey Museum we produce annually changing themed fashion exhibitions. The Olive Matthews Collection contains such a broad range of high-quality fashionable dress and textiles, dating from the early 18th century to the present, that it is a pleasure to come up with innovative ideas for displays each year. The theme for our latest exhibition, which runs until the 3rd September 2022, is flowers in dress. Chertsey last mounted an exhibition along these lines in 1997 when Dr Philip Sykas, then Assistant Curator, opened ‘The Portable Flower Garden’. I was interested in Philip’s work, and wanted to look again at the theme of flowers. We’ve added many floral pieces to the collection over the interim 24 years, many of which have not yet been displayed to the public, and these in turn complement some of the longer-standing and more familiar items housed in the Olive Matthews Collection.

There are many different reasons for the selection of a particular exhibition theme. Sometimes it’s an anniversary, such as the centenary of the start of World War 1, or women gaining the vote. At other times I’ve been inspired by the wish to exhibit a particular garment. The acquisition of a beautifully pleated Madame Grès dress led directly to our ‘Folded and Moulded’ exhibition, open from 2019 to 2020. Apart from an awareness of the previous ‘Portable Flower Garden’ exhibition, the theme of flowers in dress may also have arisen from my experience of the lockdowns of 2020/21. Never has the importance of gardens and nature been clearer to me. I felt very lucky indeed to be able to spend time outdoors in my own garden during the Covid-19 crisis and perhaps subconsciously this inspired our latest fashion exhibition.

When researching and writing the text for the display I started to think about the many reasons why flowers have held such appeal for designers and wearers over the centuries, and this was in turn influenced by my responses to flowers as experienced in my own life, including my recently renewed lockdown-enthusiasm.

The sheer beauty and variety of flowers must be the most obvious reason for their constant presence in dress. The many different types of decorative blooms we see, particularly from the 18th century onwards, reflect expanding knowledge over time as horizons broadened. Familiar native species were complemented by more exotic blooms when explorers returned from abroad with new specimens. Awareness of these novel and exciting varieties was often disseminated through published botanical illustrations. This inevitably fed into the richness and complexity of floral decoration in dress which continued over the centuries, and which is celebrated in the exhibition.

However, the enduring popularity of flowers goes deeper than the sheer number of different examples. There is something more significant about flowers themselves that makes them endlessly appealing as a source of inspiration for dress. This is derived from their natural rather than man-made status. We see flowers as entities that are not of our own creation. Whether through belief in a divine hand, a scientific understanding of the evolution of the natural world, or a combination of both, we marvel at their beauty. They have the power to appeal to our senses of sight, touch, smell, and sometimes even taste.

Leading on from that thought, there is also something about the fragility and ephemerality of flowers that hold enormous appeal. Fleeting in their existence and associated with the positivity of the summer months, flowers are somehow more precious precisely because they are only with us for a short time before they wilt and die. Flowers easily lend themselves to metaphorical comparisons with the time-limited nature of life in general and as such, they are constantly depicted in art, poetry, song, and prose. In a time before photography, reproductions and interpretations of flowers on textiles represent attempts to record and hold onto something that, in the natural world, is a fleeting and short-lived phenomenon. With all that emotion, cultural credibility, and sheer beauty in mind, why wouldn’t we want to adorn ourselves in our own more permanent flowers in textile form? These and many other thoughts persuaded me that this would be a successful theme to explore with our collection.

The gallery space, though generous, is limited by the nature of the Museum, which is located in a Georgian townhouse. We fit as many items into our displays as possible while being conscious of the need for clarity and visual appeal alongside the safety and care of the objects. In some ways, these space restrictions have helped; forcing us to use our imaginations. We try to get the most out of each display by expanding our methods of interpretation. The aim is to appeal to as many different interest levels as possible and as a result, we provide a layered approach that covers a range of interactions from a cursory walk-round to an in-depth study of individual pieces (image two).

For the ‘Blooming Marvellous’ display, we started with the immediate response of visitors to the spectacle of a wide-ranging group of floral garments. The initial impression is enhanced by the use of garlands of artificial flowers – so realistic these days – which adorn the gallery entrance and the areas above the cases. A light floral scent wafts through the room and garden sound effects add to the general ambience. With their senses stimulated, we hope to make visitors feel like they have been immersed in a floral bower.

Intrigued and inspired by their initial impressions, perhaps visitors may choose to linger and discover more about the items on display. This exhibition lends itself to a thematic approach and items are not shown chronologically. Instead, they are grouped according to the ways in which the floral decoration has been produced. A section on woven flowers gives way to printed examples. Embroidered flowers command their own area, and the exhibition closes with a selection of items featuring sculpted flowers. This approach brings variety and encourages visual and historical comparison through juxtaposition. It also provides us with the chance to explore, through text panels, the methods of creation and construction, as well as cultural and historical context, for each section.

For those who prefer not to read text panels or who want more information, a guided tour (for both adults and children) has been created which can be accessed through a smartphone via the IZITravel App. The guided tour is more detailed than the gallery interpretation, allowing us space to explore individual pieces in more depth. We have found that printed catalogues are often too costly to produce, so instead, we regularly place catalogue information online. To encourage visitors to come to the Museum in person we do not make the catalogue available publicly. Instead, all visitors are offered a postcard that bears a URL allowing access to enhanced object information which we hope visitors will make use of after their visit. We are aware that Covid19 is still a very real issue that may prevent in-person visits, so we have commissioned a virtual tour of the exhibition to allow those who cannot come in person to experience it.

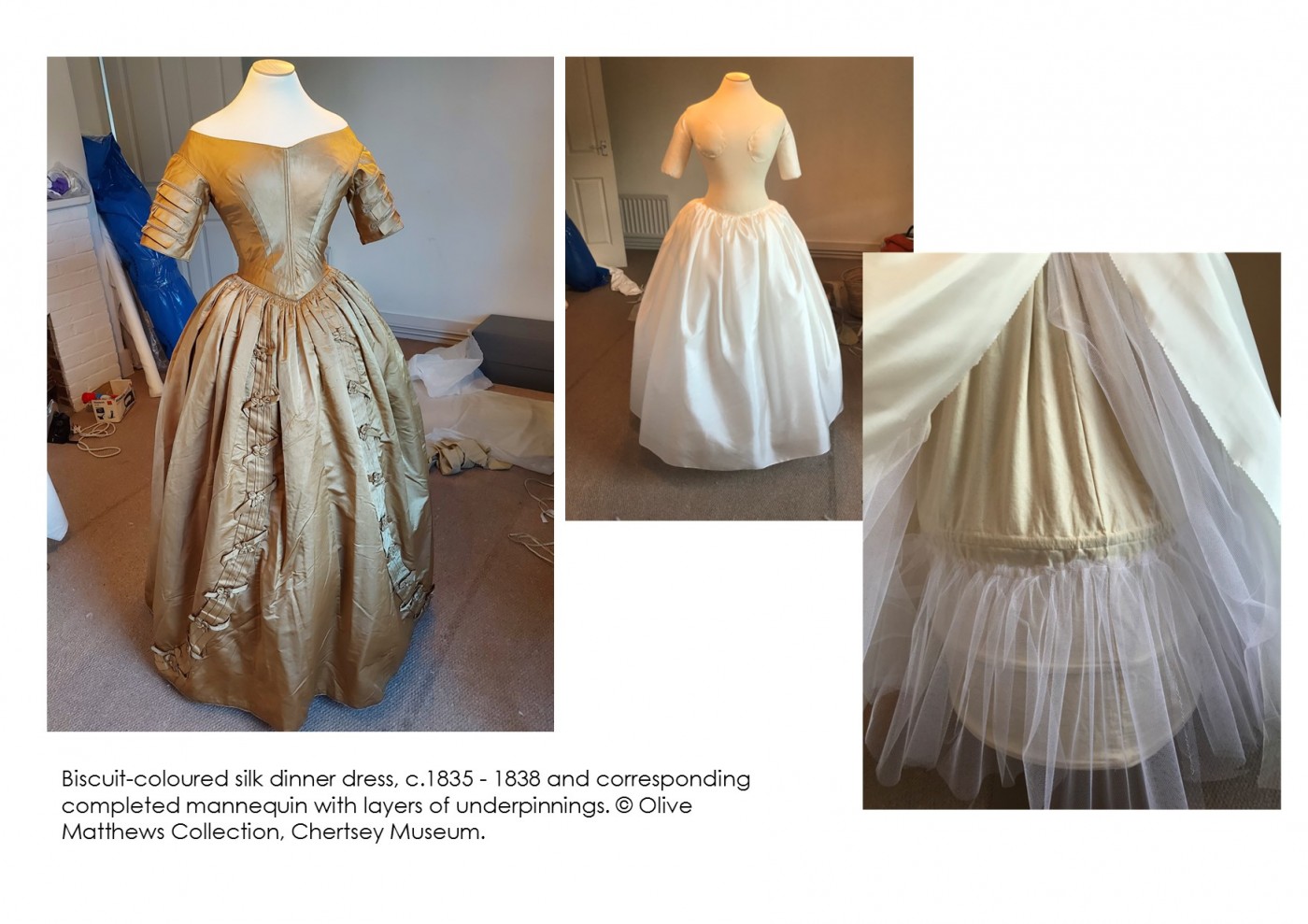

Returning to the gallery itself, for those interested in construction, or who might long to wear the items themselves, we have a wardrobe with selected replica pieces. These appeal to adults and children alike, and we are lucky to have Jane Forrest, a talented member of staff who painstakingly re-creates items for us. Jane also carries out the mounting of the original pieces. She carefully pads standard mannequins with conservation-grade wadding then covers them with cotton jersey to re-create the bodies which once inhabited the garments (image three). This is a time-consuming process that requires skill, knowledge of historical dress and an awareness of the specific vulnerabilities of each object. Due to the necessity for social distancing, the preparation for much of the ‘Blooming Marvellous’ display was carried out solo with only the mannequins and garments for company. It is easy to develop a strong affection for particular pieces due to the closeness of the relationship between garment and display technician; perhaps even more so when working alone.

Exhibition research always takes me in new and unexpected directions. There are usually moments of excitement and un-looked-for breakthroughs and sometimes the stories behind the garments can be very moving. This exhibition was no exception.

One of the pieces that form part of the ‘Embroidered Flowers’ section of the display is a beautifully embroidered Japanese kimono (image 4). My research had already revealed that this garment has an illustrious provenance – it was owned by Queen Mary. It had been worn by her during the 1920s and ‘30s and then passed as a gift to her friend Mabel Hunt, incidentally the Great Grandmother of Jeremy Hunt MP. He has since confirmed that Mabel Hunt was indeed on good terms with the Queen and received items of clothing from her. I was able to discover that it was made in Japan, but that it had been altered for use here, probably at the behest of Queen Mary. Some of these alterations relate to modesty, and to a lack of understanding of Japanese culture. Rather than retaining its original ‘wrap-around’ style, the kimono has been stitched closed with the left side tucked under the right – a style that is reserved for dressing the dead in Japan; clearly something that the royal household was unaware of. The collar also features added press studs. I suspect that these were to allow a modesty in-fill or chemisette to be added. While researching I managed to find references to Queen Mary’s kimonos in the memoirs of Mabell, Countess of Airlie. She mentions the Queen in her sitting room “in one of her lovely embroidered kimonos”. It was wonderful to have confirmation that Queen Mary owned kimonos, as, known for her rather conservative tastes, I was intrigued by her connection to this unrestrictive, delicate and exotic garment. The memoirs themselves are also a great insight into Queen Mary’s day-to-day activities and character.

Another piece, which is displayed as part of our ‘Sculpted Flowers’ group, is a beautiful wedding dress from 1916 (image 5). It is made from the softest white silk chiffon in a layered, tunic style that mimics Classical dress. Wax orange blossom flowers and leaves have been added to the bodice and train. The use of artificial and real flowers as dress adornment has a long history, but it was particularly popular during Queen Victoria’s reign when brides mimicked her use of orange blossom in her bridal ensemble. Flower making was an important industry in the Victorian era; 4011 artificial flower makers are listed in the 1891 census in London alone. The presence of orange blossom in the exhibition also gave me an excuse to talk about the language of flowers or ‘Floriography’. This was the concept of flowers embodying meanings that could communicate the status or feelings of the wearer without the need to speak. Knowledge of this language might have varied from social group to social group, but obvious flowers such as the rose or orange blossom were more commonly understood. Orange blossom is associated with fertility and purity as well as eternal love – all seen as favourable qualities for brides during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

I am keenly interested in the stories associated with garments and always try to secure plenty of information about items when they enter the collection. Wedding dresses often come with photographs of the bride as well as a clear date for original use. This particular wedding dress was worn by Eileen Browning for her marriage to Alfred Dugdale on the 25th October 1916. She was 20 years of age. I was sad to hear that Eileen had tragically died in childbirth just a year later in 1917. Her mother kept the dress carefully wrapped in tissue paper and treasured it as a memento. The dress was kindly donated by her descendants.

Finally, while researching a wonderful pink tulip-shaped evening gown by Bruce Oldfield, I wanted to see if I could contact the designer to gain more insight ahead of interpreting it for the exhibition (image 6). I decided to take a chance and send an email via his website. To my surprise and delight, I received a response almost immediately from Bruce Oldfield himself asking for photographs which I duly sent! This was the start of an email dialogue between us. Commenting on the tulip dress he said: “It would have been the kind of dress that I would have encouraged Princess Diana to wear in the early days of our working together (unsuccessful)”. Bruce Oldfield famously designed for Princess Diana for 10 years from 1980. Discussing his work at the time when this dress was designed and produced, he said that he “was never commercially driven and enjoyed experimenting with shapes and cuts, eschewing the traditional way of constructing garments and always relating design to hand techniques in dressmaking rather than be driven by what the machine demanded”. When mounting the dress we were struck by the high level of workmanship evident in the construction which is on a par with haute couture. He commented that it “does have a certain couture look to it”. He went on to state that “The simplicity of this dress would mean it needed to be made one by one, it isn’t a production line dress”. He was also able to confirm the date of the dress which was made between 1980 and 1982. The chance to hear details about a garment direct from the designer is always a huge bonus, particularly one who has been so influential in British design. What could be more perfect for a gown that fits so neatly with our theme and is a real focal point in the exhibition!

Grace Evans is the Keeper of Costume, The Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum.

Image credits:

1. Blooming Marvellous Exhibition, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum

2. Blooming Marvellous Exhibition, opening case, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum

3. Mounting a biscuit-coloured dinner dress, 1837 – 1839, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum

4. Detail of Japanese embroidered kimono, 1920 – 1930, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum. Image by John Chase Photography

5. Silk chiffon wedding dress, 1916, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum. Image by John Chase Photography

6. Evening gown by Bruce Oldfield, 1980 – 1982, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum. Image by John Chase Photography

Image gallery

Image 1. Blooming Marvellous Exhibition, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum

Image 3. Mounting a biscuit-coloured dinner dress, 1837 – 1839, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum

Image 5. Silk chiffon wedding dress 1916, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum. Image by John Chase Photography

Image 6. Evening gown by Bruce Oldfield, 1980 – 1982, © Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum. Image by John Chase Photography