- youtube

- bluesky

- Home

- About

- Costume Journal

- Membership

- Conference & Events

- Grants & Awards

- News & Social

In this week’s blog post, Fashion historian Jenny Frances Mearns takes us behind the scenes of the ‘Fashioning Our World Project’ at The Salisbury Museum. A project that focuses on historical dress alterations in order to uncover a garment’s story, change the way we see ‘imperfect garments’ in a museum setting and inspire more sustainable fashion choices in the future.

Museums can often collect and display exemplary examples of historical clothing, complete and pristine, free of flaws. However, imperfect garments hold nuances of the human experience, reflecting changes in the wearer’s sartorial decisions, providing clues to embodied activities performed. These imperfections can be present in the form of repairs, darns, patching, alterations, and even repurposing. A recent project at The Salisbury Museum aims to examine these practices to uncover stories of sustainability to inform and inspire future generations.

The Fashioning Our World project launched at the beginning of 2022 and will culminate in an exhibition in 2024. Supported with funding from the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund delivered by the Museums Association, the project aims to engage with communities, specifically young people (ages 11-25) to think differently about the fashion system, to treasure what they already have rather than perpetuating the cycle of fast fashion. Through discovering these stories of sustainability, communities can be inspired and put into practice skills of repair and repurposing offered in workshops as part of the project, thereby distributing knowledge and effecting positive social change. Professor and author Janet Hethorn eloquently surmises the relevance of exploring past practices of sustainable fashion for today:

‘To answer the question “why now?” for sustainable fashion, we must first look to the past. How has sustainability come and gone throughout the history of modern fashion, from 1600 until today?’[1]

In 2020 the Fashion Gallery at the museum was relaunched, with the completion of the predecessor to Fashioning Our World, the Look Again project. Working specifically with young people the Look Again project sought to redisplay and subsequently relaunch the Fashion Gallery at the museum, the results of which remain for visitors to enjoy today.

My involvement with the Fashioning Our World project began as part of a work placement for my Curating, Collections and Heritage MA, which I have since completed at the University of Brighton. Initially I was tasked with investigating the fashion collection to identify objects that evidenced sustainable fashion practices, made tangible in the form of mends, repairs, repurposing and alteration.

In order to identify items within the collection that evidenced such practices, I began my search by looking through supporting documentation, such as accession cards and the museum’s collections database. This proved to be challenging, as past museum practices historically privileged ‘perfect’ garments and objects, so therefore whilst repairs, mends, alterations, and repurposing were certainly present in the collection, often such information was omitted from the supporting documentation. However, being new to the museum and unfamiliar with the collection, this proved to be a useful initial avenue of investigation.

The fashion collection at The Salisbury Museum comprises over 3,500 objects, with many of these items holding connections to the locality of Salisbury and the surrounding areas. Indeed, these collecting practices are reflected in the Collections Development Policy of the museum, with priorities for future collecting stating:

‘Costume and textiles worn, made by or associated with local people are collected, particularly material with display potential. Working people's and men's clothing is particularly needed to fill gaps in the collection’.[2]

This statement illustrates the importance of local museum collections remaining relevant and representative of the localities and communities to which they serve. However, this also demonstrates the dichotomies in collecting practices between garments that accurately evidence embodied activities performed by the wearer(s), yet retain aesthetic appeal or structural integrity (often both) in order to be considered for display.

One such item in the collection discovered whilst working on the Fashioning Our World project that illustrates some of these issues, is a repurposed women’s bodice front. Originally a male waistcoat dating from the eighteenth century, it was repurposed in the late nineteenth century to form a functional women’s bodice front. By intersecting gender, this item initiates questions on the categories into which objects, garments and their wearers are placed, both within a social sphere and in the wider context of museum collecting practices.

The fine embroidery and silk fabric of the garment indicates that the original waistcoat would have belonged to and been worn by an affluent male. Looking to clues as to the origin or thought process behind the transformation from male to female, from waistcoat to bodice front, sadly the museum documentation does not provide any indications.

However, the bodice front has been executed to a high standard, indicating that the repurposing was thoughtful, planned, served a requirement, and was intended to be functional. The bodice has been constructed by utilising the front panels of the original waistcoat, retaining the original buttons and buttonholes. The original pockets and embroidered pocket flaps also remain, yet in the process of repurposing the pockets have been rendered redundant due to the machine stitched binding on the edges of the garment encapsulating the pocket flaps. For the bodice front to be worn, the side edges feature neatly executed handsewn eyes, onto which the side panels of the wearer’s bodice would hook onto. To accommodate the female figure, each side features two machine stitched darts, thereby creating shaping, and executing a fashionable late nineteenth century silhouette.

This piece is a key object for the Fashioning Our World project, as sustainable fashion practices are evident in the form of repurposing, resulting in a compelling narrative. In addition, the repurposed waistcoat also possesses aesthetic appeal, and as highlighted in the Collections Development Policy of the museum, has display potential.

Whilst this piece is viable for display, other pieces discovered in the collection whilst working on the project may potentially be unlikely to meet the criteria required to fulfil the demands of display. Through investigating garments and objects within the fashion collection at the museum, the dichotomies and tensions between public display and museum storage become apparent. This in turn reflects arguments proffered by authors Mirjam Brusius and Kavita Singh in the following quote:

‘Museums have long been arbiters of value. To call a thing ‘museum-quality’ is the ultimate stamp of approval of its worth and significance. But the public perceives not what the museum collects but what the museum puts on show. The idea that the museum values most highly what it displays most prominently has led to arguments about what should be exhibited […]’.[3]

The presence of alterations, repurposing, mends and repairs may have previously rendered such garments flawed, imperfect, and therefore not deemed sufficient for display. However, by giving visibility to these garments, stories and narratives usually contained within collection stores, the Fashioning Our World project readdresses concepts of value, unlocking these fascinating stories of sustainability and ingenuity for the future.

Bibliography

[1] Janet Hethorn, et al. Sustainable Fashion - Why Now? A Conversation about Issues, Practices, and Possibilities (New York: Fairchild, 2008) 7.

[2] ‘Themes and priorities for future collecting’ The Salisbury Museum Collections Development Policy, 2020, point 4.8, pg 13.

[3] Mirjam Brusius, and Kavita Singh, Museum Storage and Meaning: Tales from the Crypt, (Routledge, London, 2018) 3.

Further Reading

Fletcher, Kate, et al. Fashion & Sustainability: Design for Change. London: Laurence King, 2012. Print.

Mida, Ingrid, and Alexandra Kim. The Dress Detective: A Practical Guide to Object-Based Research in Fashion. Bloomsbury, London, 2015.

Jenny Frances Mearns has recently completed an MA in Curating Collections and Heritage at the University of Brighton. She works as a Collections Assistant for The National Trust and continues to volunteer on the Fashioning Our World project at The Salisbury Museum.

Follow Jenny on Instagram (@jennyjenfran) and Twitter (@jennyjenfran). And visit her website (www.whimandweft.com).

The Costume Society is a lively, friendly organisation whose aim is to promote the study and preservation of historic and contemporary dress. If you would like to join our passionate community become a member today.

If you work for a small museum seeking to conserve and display historical dress and textiles please have a look at the Grants and Awards The Costume Society offers such as the The Daphne Bullard Grant or The Elizabeth Hammond Grant

Image gallery

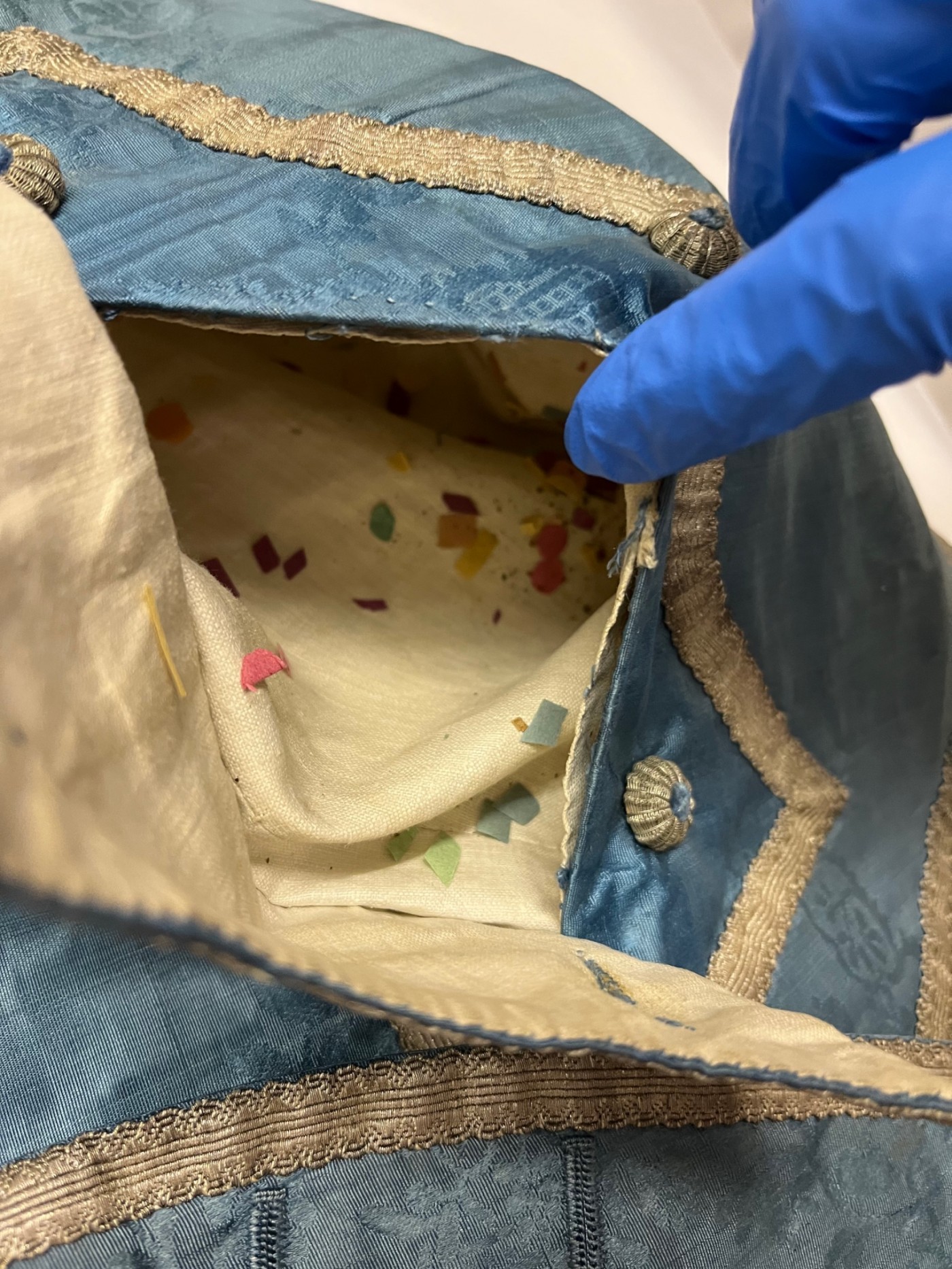

Coloured paper confetti inside a pocket of a repaired eighteenth-century male waistcoat. The Salisbury Museum.

Fabric remnants and unpicked fabric pieces from an 1880s dress made by Mrs James of 2 Hanover Square London. The Salisbury Museum.

Interior of an 1850s wedding bodice, enlarged at the side seams by insertions of fabric panels. The Salisbury Museum.

A women’s bodice front repurposed in the 1880s from an eighteenth-century male waistcoat. The Salisbury Museum.

A women’s bodice front repurposed in the 1880s from an eighteenth-century male waistcoat. The Salisbury Museum.

A women’s bodice front repurposed in the 1880s from an eighteenth-century male waistcoat. The Salisbury Museum.