- youtube

- bluesky

- Home

- About

- Costume Journal

- Membership

- Conference & Events

- Grants & Awards

- News & Social

In this week’s blog, professor and curator, Amy de la Haye, writes about the first exhibition dedicated to British folklore dress ‘Making Mischief: Folk Costume in Britain’, discussing the ideas and ethics that underpin the exhibit; the teams working processes and Simon Costin’s, director of the Museum of British Folklore, exhibition design.

Making Mischief: Folk Costume in Britain is the first exhibition to foreground this vibrant and highly politicised area of the nation’s dress heritage. It is also the first exhibition I have worked on (as co-curator) when I have not been the subject specialist. That credit goes to my erudite curatorial colleagues Simon Costin (director) and Mellany Robinson (special projects manager) of the Museum of British Folklore (MoBF). It is the second exhibition I have not installed (the other was Ravishing: The Rose in Fashion at the Museum at FIT in New York, due to the pandemic).

However carefully you plan an exhibition, it is not until you see ‘your’ objects brought together for the first time, that you can determine whether they will work together as intended. Or, indeed whether they will surprise you by forging new relationships and stories with unexpected others. For me, experiencing and trying to accommodate this, is one of the most thrilling stages of making an exhibition. I was thus doubly devastated to find myself in hospital as the team crafted Making Mischief: Folk Costume in Britain into the gallery spaces at Compton Verney. And, as such I cannot relate, at first hand, these encounters.

I can provide insights into the evolution of Making Mischief; our impassioned determination to make the project happen; the ideas and ethics that underpin it; our working processes and Simon’s exhibition design. I will initially share our definition of folk costume and provide some subject specific context.

We define folk costumes as the dressed appearance (including body adornment, jewellery, cosmetics, etc.) worn by participants to celebrate a particular date, season, person, occasion or story. A huge variety of folk customs, each with their own specific costumes, are celebrated from Scotland’s northerly isles to England’s south coast. These have been greatly enriched by the folk customs celebrated by immigrant communities and newly emerging customs. Folk festivals – in their various guises – are inherently subversive, heavily aligned towards radical left wing and environmental politics and alternative religions. From the Puritans in the 17th century to the present day, gatherings have been systematically suppressed by the church and state; deemed as a threat to civil order and/or the political status quo.

Folk costumes are usually home-made or customized, with makers re-purposing pre-existing materials and items drawn from the natural world. They communicate group membership and individual identities. Whilst they can serve as holders of deeply personal, familial and community meanings, the inherent ephemerality of many folk costumes (flowers and leaves perish), the fact that they have been dismissed for not being `well-made’ and have little financial ‘worth’, they have – all too often – been dismissed and discarded. This might help explain why Britain – unlike many European countries – does not have a state funded museum dedicated to its rich folk culture history and living heritage. Rather than simply rue this absence, Simon took assertive action to ensure this vital historical and living heritage would be captured and safeguarded by establishing the MoBF in 2009. Since then, as they have no fixed venue, he and Mellany have staged 14 exhibitions hosted by other organisations. Making Mischief is the latest of these. Titles are critical and usually the subject of extensive debate; this was Mellany’s proposal which we all immediately felt was right’.

The project materialised following a serendipitous meeting with Mellany on a train platform in 2019. She explained that she and Simon had been planning an exhibition on folk costume. I was of course familiar with Simon’s acclaimed set design and fashion work I knew he was director of the enchanting Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in Cornwall. As alternative and popular cultures have always occupied a central role within my work, and I am compelled by idiosyncratic independent museums, I asked if she and Simon would like to collaborate with myself and colleagues from the University of the Arts London research Centre for Fashion Curation (CfFC, of which I am joint director, with exhibition maker Judith Clark). I subsequently introduced them to Dr Ben Whyman, manager of CfFC (and Costume Society UK Vice-chair Grants and Awards) and administrator Bre Stitt. Due to the pandemic, our meetings took place online.

From the outset, we determined to challenge misconceptions that folk culture in Britain is exclusively white, heteronormative, male-dominated, rural, nostalgic and ‘fixed’. We decided to approach Compton Verney (CV, Warwickshire) which houses the most significant collection of folk art in Britain, but no costume. Simon and Mellany had an existing relationship with CV as they had previously staged an exhibition on fireworks there. Abbie Viner (now Head of Cultural Programming) and Oliver McCall (curator) responded positively to our proposal, necessarily pitched online, and offered us their February 2023 slot. With the support of Tamsin Ace, Head of Cultural Programming at LCF, we also secured the Spring 2024 slot at LCF’s new Stratford site.

Led by CfFC, the three institutions submitted a bid to the National Lottery Heritage Fund (NLHF) which stressed the vital need to capture and preserve this vital historical and living, intangible cultural heritage (defined as the creative and other expressions, knowledge and understandings practiced by communities and individuals). We applied to the #DynamicCollecting funding stream, which the NLHF define thus: ‘A dynamic collection: is used by, and meaningful to a wider range of people, enables different perspectives to be heard and a variety of stories to be told; is actively reviewed’ (www.heritagefund.org.uk). Writing the funding bid involved a huge amount of highly detailed work. Very fortunately we were awarded £249k to develop events, activities, training opportunities and safe spaces for local and marginalised communities to explore their folk heritage, enjoy activities and workshops and learn new skills.

Making Mischief: Folk Costume in Britain brings together just a selection of the rich diversity of folk costumes worn across the length and breadth of Britain in the past and present day. These include costumes created and worn by various morris sides; mummers and longsword dancers; Abbot Bromley Horn Dancers; May Queens (including a costume designed by illustrator Kate Greenaway); at the Notting Hill and Leeds carnivals; Jack in the Green Festival; and children to celebrate Orkney’s Festival of the Horse. These loans were primarily secured by the personal connections that Simon has made with folk participants over the last 15 years. Wherever possible we have foregrounded the voice of the wearer or maker – via spoken and written narratives.

Throughout the exhibition, costumes are contextualized by detailed texts and displays of snapshots, professional photographs that include Henry Bourne’s dynamic portraits, items belonging to folk participants, a selection of paintings and objects drawn from Compton Verney’s collections; the English Folk Dance and Song Society and Whiteland College’s May Day archive. Visitors can also choose to enter a room to obtain an immersive festival experience which draws upon 60 years of research filmed by folk specialist Doc Rowe and edited by filmmaker Ruth Hogben.

Our curatorial ambitions have included confronting and engaging with complex and highly controversial issues, most notably the practice of blackface amongst some morris sides, a practice that the Joint Morris Organisations’ banned in 2020. As part of the NLHF bid we have appointed an EDI panel to support and advise on how we interpret and engage with equity and diversity. A section in the exhibition presents objects, which include some of the blackface morris dolls from MBoF supported by critical discursive texts. Whilst recognizing this could cause distress, we hope our approach will foster greater tolerance and understandings.

Making Mischief Folk: Costume in Britain has already attracted major press interest and has been featured and reviewed by media sources including the BBC, The Observer, The Guardian, World of Interiors, Selvedge, SHOWstudio, The Spectator, Financial Times and Hole & Corner. We hope the widespread interest and critical acclaim the exhibition has received means that we might now secure a prestigious publisher (the book proposal we developed in 2020 was rejected due to a perceived ‘lack of interest’).

We are now in the process of planning the London iteration of the show (which we will probably re-title) which will have a significant local emphasis and will include student responses. The NLHF funding bid has permitted us to work with local schools and communities; create outreach projects and exhibit costumes worn by local marginalized communities. The projects will draw upon Making Mischief’s core themes of sustainability, the environment, sexuality and identities, craft skills and how these are brought together as vibrant community expression.

The long-term ambitions for the project are to secure funding for a fixed venue for the MoBF so that the collections can be made publicly accessible and, ideally to achieve museum accreditation status in order to apply for future funding. We also hope to raise awareness, capture and preserve the vibrancy, resilience and diversity of folk cultures and costumes within Britain’s past, current and future heritage.

Make sure to click on the images in the image grid below to read detailed captions about about the images.

Bio:

Amy de la Haye is Professor of Dress History & Curatorship and joint director (with Judith Clark) of the research Centre for Fashion Curation at London College of Fashion. Formerly, she was Curator of 20th Century Fashion at the V&A where her exhibitions included ‘Streetstyle’ (1994). Recent exhibitions include ‘Ravishing: the Rose in Fashion’ (with Colleen Hill) at the Museum at FIT (New York) and ‘Wild & Cultivated: Fashioning the Rose’ (with Simon Costin) at London’s Garden Museum. Most current is ‘Making Mischief: Folk Costume in Britain’ , with Simon Costin and Mellany Robinson, at Compton Verney which she reviews here.

Check out Amy’s Instagram and her UAL research profile. Click here to check her many books she has written and edited.

Making Mischief: Folk Costume in Britain is on at Compton Verney until 11 June, 2023. The admissions tickets are £18 (without Gift Aid). 19-25 year old tickets are £10. Children under 18 and Compton Verney members go free. Make sure to book tickets for the curators talk on the exhibition, on the 5th of May!

Compton Verney is a parish and historic manor in the county of Warwickshire, England. The manor house has 120 acres of beautiful grounds. Compton Verney extensive collections range from British folk art and portraits to Chinese and Neapolitan art. Make sure to check out Compton Verney’s Facebook, Instagram and twitter page.

Image gallery

Simon Costin donning his Museum in a Hat designed by Stephen Jones. Courtesy: the author

He commissioned it to wear during his year-long, micro-museum caravan tour of the UK to raise awareness and funds for the Museum of British Folklore (est. 2009).

Jack in the Green, Hastings, East Sussex. Simon Costin participates in this festival costumed as a self-defined Gay Bogie. Courtesy: Margo Galandina

In order to make explicit the renegade nature of folk cultures, the back drops – designed and made by Simon – were inspired by protest banners and graphics. The mannequin faces are rendered neutral by covering them using brown paper and tape. Simon was inspired by the old medicinal brown paper and vinegar remedy which mended Jack’s crown in the children’s nursey rhyme Jack and Jill.

Dr Ben Whyman covering for me during the installation. Courtesy: Laura Thornley, research assistant who supports CfFC’s special projects.

In the main entranceat Compton Verney visitors see a sculptural, brilliant pink, costume designed and installed by Clary Salandy from Mahogany Carnival.

The dark green walls set an oppressive mood. Exhibition designed by Simon Costin. Courtesy: Simon Costin

The exhibition galleries are arranged broadly chronologically, at the point following the execution of King Charles 1 (1649), a time when the English parliament was led by radical Puritans. A small portrait of Oliver Cromwell, painted by Samuel Cooper in 1657 and drawn from the museum’s collections, is the first object visitors experience. It is perhaps an unexpected choice, suggested by Mellany, that effectively sets the oppressive mood; Simon reinforced this by painting the walls a dark shade of green. As visitors move through galleries devoted to Jacobean times and the Victorian sanitisation of folk cultures – including May Day - the green tones are lightened. In the main final gallery the lightest green is used to suggest the greater freedoms of the present day. This is the Victorian Gallery. The May pole (here recreated by Simon) was, in Puritan times, deemed a focal point for subversion. Following the restoration of the monarchy, they became freedom. The costumes (including one designed by the illustrator Kate Greenaway) were borrowed from the May Day Archive at Whiteland College.

Photograph albums were borrowed from the May Day Archive at Whiteland College. Courtesy: Simon Costin

These meticulous and skillfully costumed dolls (including carved wood and leather clogs) form part of the Museum of British Folklore’s ongoing project Morris Folk, launched in 2013. Courtesy: Simon Costin

A standard cloth doll was sent to morris sides across the country with an invitation to dress it in a miniature replica of their costume and return it to the museum. Today, there are nearly 250 dolls in the collection. Simon used the bunting to evoke the village green and community-led celebrations.

Main exhibition gallery. Courtesy: Simon Costin

Simon has created a flexible modular design using scaffolding poles that can eventually be recycled. The costume in the form of a vibrant pink butterfly was designed by Hughbon Condor for the Leeds Carnival.

The Festival of the Horse, children’s costumes, Orkney. Courtesy: Simon Costin

Simon had made a previous visit to experience the festival and had already made friends there. Moira Budge and Anne Peace, informal custodians of the festival’s heritage, welcomed us and made introductions. It was a great treat to be shown the oldest surviving costume which dated from 1935 and had been further decorated with coronation memorabilia. The family welcomed our interest and shared their stories, but simply could not bear to let their precious items leave the island.

Costumes (details) borrowed from the outstanding archives of the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS). Courtesy: Simon Costin

The jackets with ruched detailing were worn by Grenoside sword dancers. The bold, intuitive creativity of these appliquéd garments – the jerkin – one of several – may relate to a mummers tradition (mummers performed in exchange for money, food and drinks). The cotton appliqué top and trousers (possibly my favourite object) outift is a Sleights Plough Stots costume.

On the left is a Padstow ‘Obby Oss’, on the right hobby horse. Courtesty: Margo Galandina

The hobby horse was a common feature of early morris dancing and horses remain a prominent feature within any folk customs. On the left is a Padstow ‘Obby Oss’ which takes to the Cornish streets on May Day EFDSS); on the right a Hoodening Horse which is mainly local to north eastern Kent (MoBF).

A smother coat. Courtesy: Simon Costin

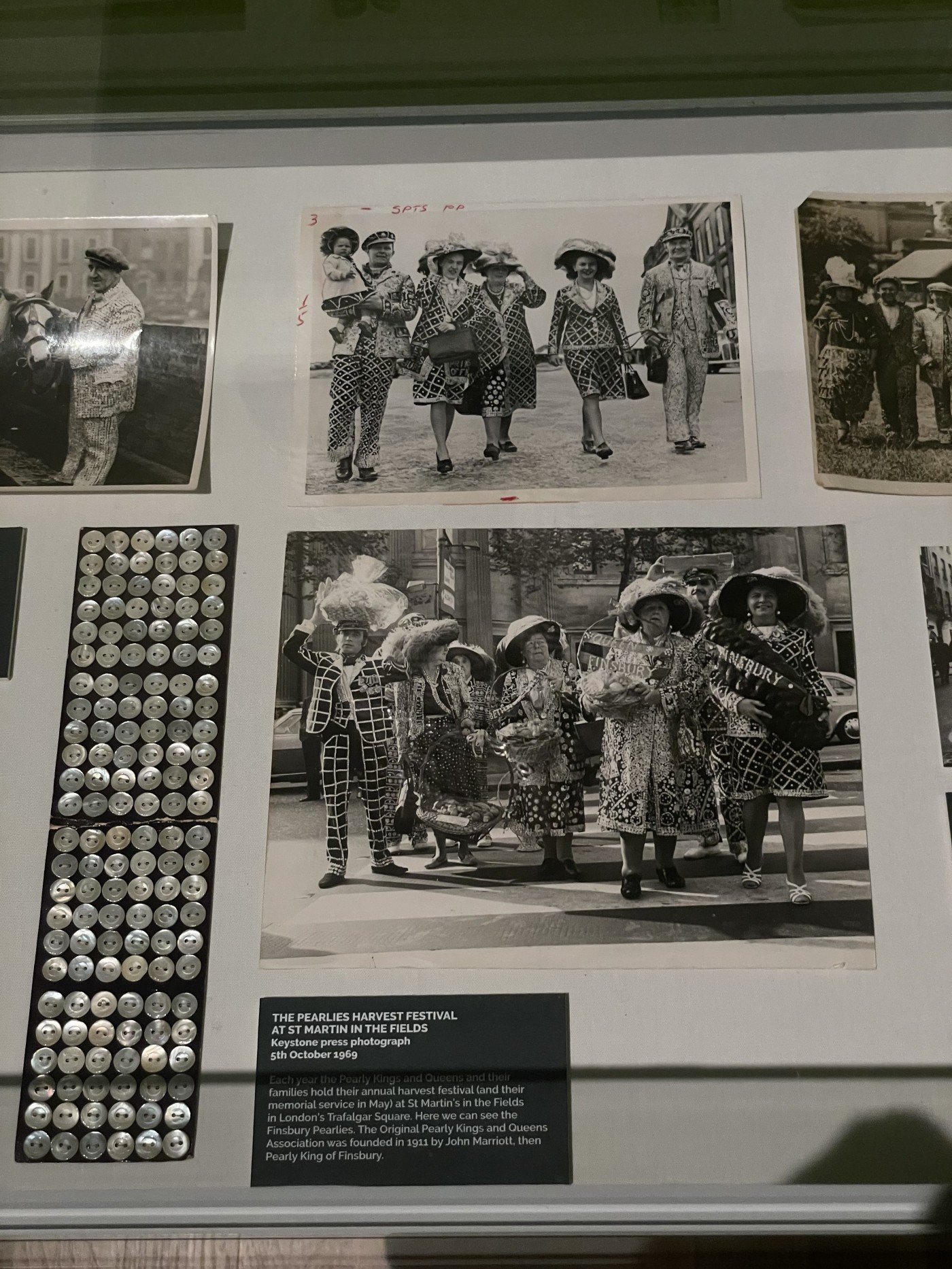

London’s Pearlies decorate their own costumes using buttons to create a variety of patterns and symbolic designs. A smother coat is the name of a garment entirely covered in buttons. Jacket lent by Diane Gould.

Detail of photographs and buttons display that supports the Pearly costumes. Collection MoBF. Courtesy: Margo Galandina

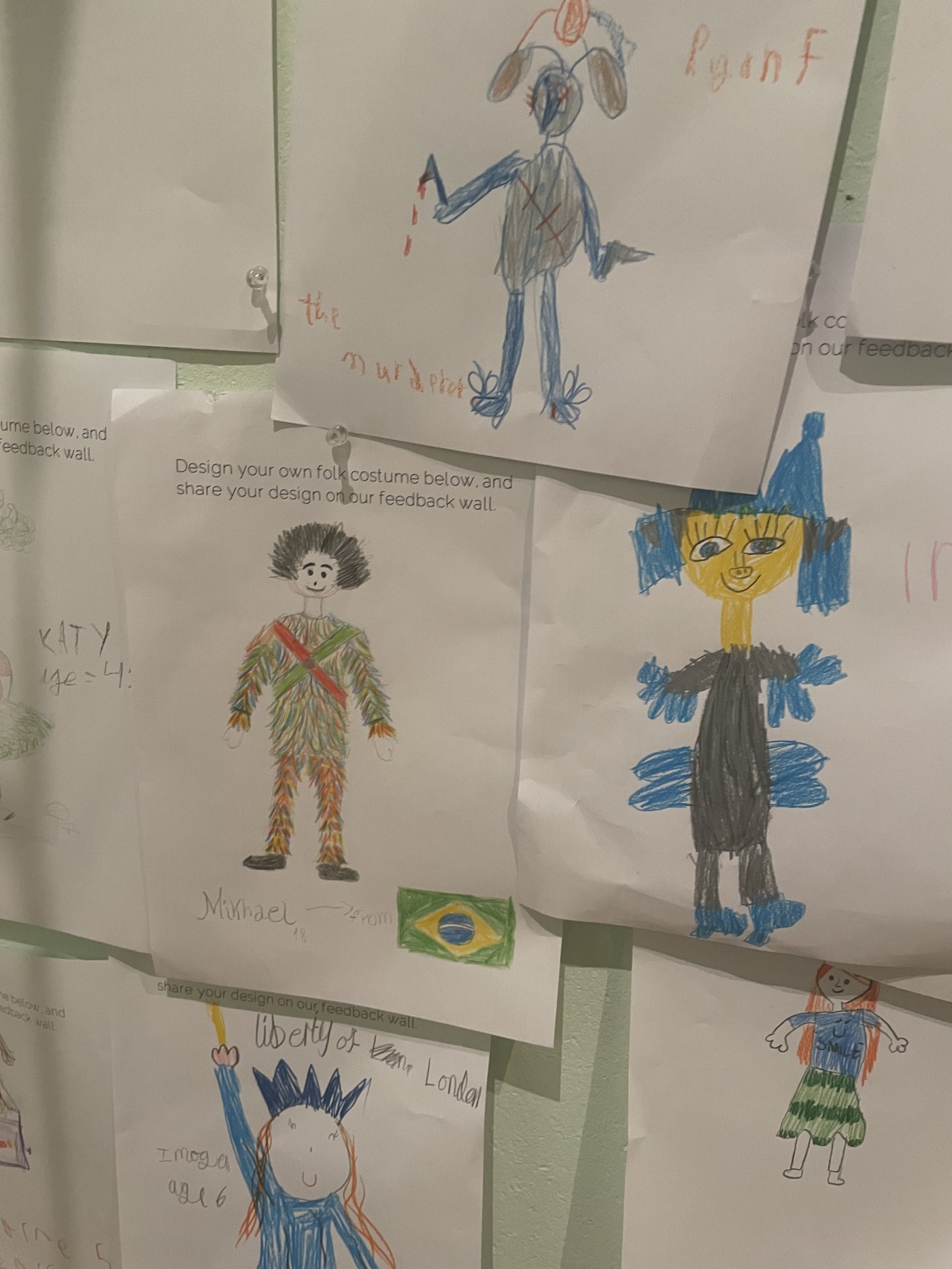

Within the first two weeks of opening there were hundreds of costumes drawn by adults and children. Courtesy: Margo Galandina

The costumes have also inspired a number of fashion designers but we made a conscious decision to not feature these in the exhibition.