- youtube

- bluesky

- Home

- About

- Costume Journal

- Membership

- Conference & Events

- Grants & Awards

- News & Social

In this week’s blog, Stephanie Richards, Costume Curator at Henfield Museum, discusses the ingenuity behind dressmaking in World War Two and how women made the best use of the fabrics they could find be it curtain material or parachute Silk.

During the Second World War a good deal of Government information was forthcoming on clothing, feeding and protecting your family. Much was written to educate, inform and advise the public on how to do these things. Not the least on the question of how to ensure every family member was adequately clothed. The Ministry of Information issued pamphlets like ‘Make Do and Mend’ (1943). This is packed full of instructions to enable you to patch, reknit, shorten, lengthen and revitalise clothing. ‘Mrs Sew and Sew’ (1944 Ministry of Information) used animated British Pathé films to suggest how simple it was to turn unused clothing into new creations. The frugality of this course was emphasised too, as it saved on your coupons. Articles in women’s magazines told you how to adapt a worn out skirt into a pair of trousers for a child or refashion a suit of your husbands into a suit for the lady of the house.

In war time ‘Doing It Yourself’ became an essential part of being clothed. Driven by cost and necessity making your own clothes was already a fixture of many peoples lives. Home dressmaking had always been linked to disposable income, but now you needed ingenuity as well to make the best use of the materials you could find. Scarcities and strictures on wartime supplies took making your own clothes into entirely different territory. Shop-bought clothing was still available but prices and limited availability were problematic. There were shortages of (amongst others) cloth, buttons, elastic, wool and thread.

The introduction of clothes rationing on 1st June 1941 meant that how many coupons you had was now an additional factor for purchasing material. If you could find any that is. Non rationed fabrics (black out material for instance) were sought after. Being able to make a dress, repair a sock or patch a blouse became both a duty and a necessity. It was seen as patriotic to repair and refurbish. Not just a sterling way to act in war years, but often the only option available to people.

Recycling existing garments was a popular option. Although the section on repurposing men’s clothing into women’s in ‘Make Do and Mend’ makes the reasonable point that before you begin, you must be sure that he wont want his clothes again after the war. No matter how clever you were with a needle, the material to sew with needed to be found. Alternative sources of scarce coupon heavy fabric were duly sought.

Arguably the most iconic alternative options for home dressmaking were parachute silk and furnishing fabric. The costume collection at Henfield Museum has examples of such pieces from the 1940s. Namely two pieces of parachute silk clothing and a cyclamen pink wedding dress. Between them they illustrate choices made by those who lived through the Second World War. Choices that may have been forced on them, but that nevertheless showcase their skill and imagination.

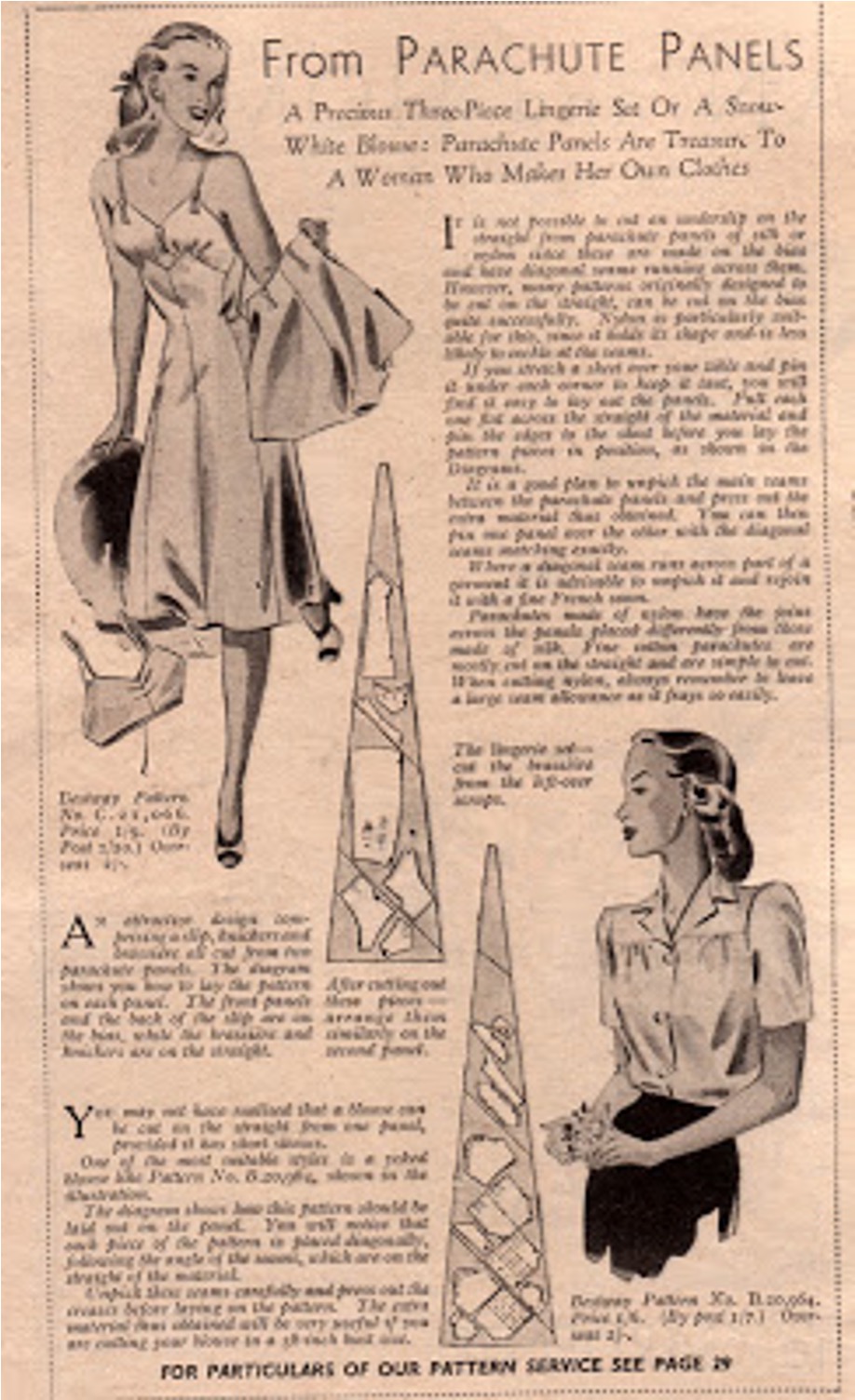

Parachute silk was not always silk. The war cut off supplies of silk from Japan and so the limited stocks available were targeted towards military use. However these restricted quantities of silk were not sufficient on their own, so from June 1942 nylon was used for white personnel parachutes. This white nylon fabric was fluid, lightweight and soft. These useful properties were not lost on makers and so panels of the fabric found a new purpose; to make slips, French knickers, nightgowns and wedding dresses. A single personnel parachute panel was 40” (1m) at base, reducing to 5 1/8th (130mm) at the top. Maximum length of panel 158” (4m). Women’s magazines had features like the one illustrated showing how to get the maximum use out of a single parachute panel.

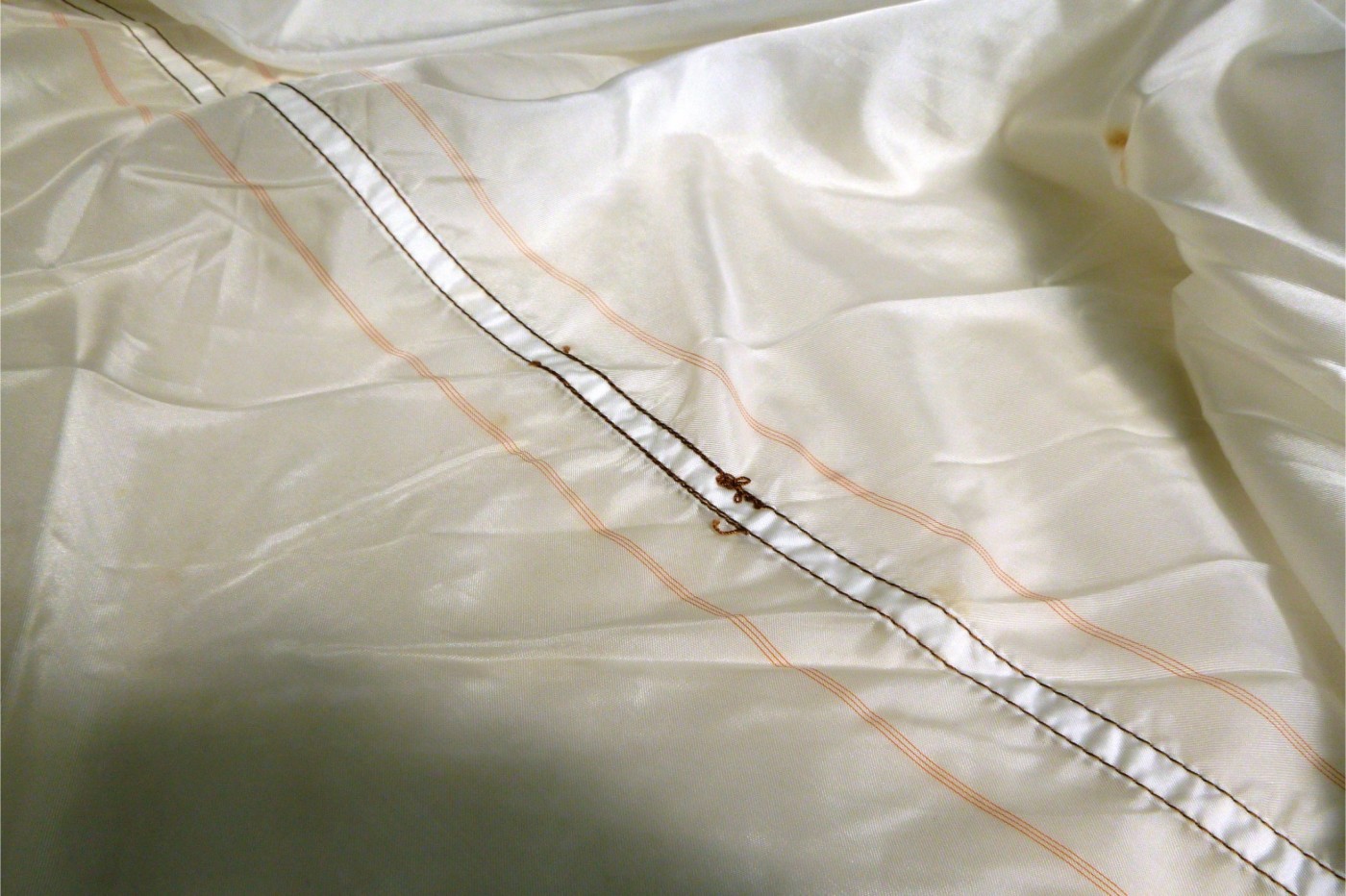

Apocryphal stories suggest that parachute silk could be obtained under the counter, from the black market or as faulty panels from a parachute factory. This does suggest an unfeasibly high level of substandard or purloined items. There were some genuine exceptions to a parachute being reused. If it had been used to ditch in the sea the salt water compromised the fabric and it could no longer be used as a parachute. Whatever the truth of ‘everyone’ having something made from parachute silk and ‘everyone’ knowing where to lay their hands on some, it was against the law to use it for civilian purposes. From 1945 it was sold off coupon through Army Surplus stores. Defective pieces did exist as standards of stitching and construction were rigorous.

These examples of parachute silk (actually parachute nylon) garments from the Henfield Museum collection show examples of what might be made from a parachute panel. (Please refer to the imae grid below). The nightdress and blouse were made by the same person. The only provenance the museum has for these is that they were made by the donors mother ‘in the 1940s’. Both are a combination of hand and machine stitching.

The seam of the parachute panel is visible diagonally across the skirt. A tie belt of folded parachute fabric has been added at the waist. The stitching for the original channel for cords on the parachute can be seen on the fabric of the belt. Careful hand embroidery adds colour to the neck line and the frill on the bodice. Then this smart short sleeved blouse which displays the makers skill with drawn thread work. The cuffs of the short sleeves are decorated with the same design. The waist is elasticated.

It was not just parachute material that was pressed into service. Homemade clothing drew on many different materials for example this wedding dress made from curtain material. Sewn in 1940 before clothes rationing began, the chosen cyclamen pink is striking. The addition of the blue and silver details make a colourful combination.

This dress was made by the bride, a milliner by profession. The fabric is described at the time as ‘cyclamen pink’. The blue insert on the bodice appears to be crêpe and silver lamé provides edging and backing detail. The level of detail extends to the ends of the short sleeves being trimmed with the same blue and silver.

The bride also embroidered her veil and the threads used for the designs match the colours in the dress exactly. Thanks to the newspaper report, we know that her coat was silver grey, trimmed with grey lamb and she wore cyclamen shoes and carried a bouquet of anemones. Her ‘halo headdress’ has sadly not survived.

The museum has some detail on the wedding day, including a newspaper report. This enables us to know a little about the bride who chose such an vivid palate and went on to sew such a beautiful dress and veil. Her choices at a time of austerity speak to her determination that her wedding would be as she wished it. The dress and veil expand both the social and sartorial information that is passed on to us. The bride and groom were Margaret and John. It mentions that the groom was a member of the Gemmological Association in civvy street and that Margaret possessed a diploma from the Paris Academy of Millinery, Bond Street, W1. After Margaret’s demise I was privileged to visit her house to receive the wedding dress and veil donation. I interviewed her niece and heard memories of what Margaret was like and how happy the marriage was.

To be able to examine and reflect on work accomplished during such a turbulent period in history is a privilege. The culture of making do and mending, of remaking and recycling outlasted rationing and war. In these garments we can see reflected not just the skill of the makers but daily life and social history. These examples help us to realise the ingenuity shown by the people who clothed themselves and their families by making use of what they could buy, press into service or repurpose. I salute them.

Further reading

Jayne Shrimpton - Fashion in the 1940s pub Bloomsbury 2014

Julie Summers - Fashion on the Ration pub Profile 2016

Geraldine Howell - Wartime Fashion pub Berg 2012

Stephanie Richards is a writer and the costume curator for Henfield Museum, West Sussex. Her current research interests are split between Utility labelling codes and examining the links between clothing in the collection and the village of Henfield. Her online and print articles promote the costume collection and the museum. Published costume work includes articles and serials for magazines here and in Australia.

Make sure to follow Stephanie on Facebook, Instagram and twitter, where she often posts about captivating garments she comes across. Also be sure to check out her blog!

To read more of Stephanies work on Parachute Panels click here.

Grateful thanks to Worthing Museum and Woman and Home Magazine for permission to use their images.

Henfield museum can be found on Facebook and Instagram, or go to their website.

Are you fascinated by the stories behind historical clothing too? Do love to find vintage garments? Or do you just want to learn more about fashion history? Why not come join our friendly and passionate community here at The Costume Society. Become a member, click here to join today!

Image gallery

Woman and Home Magazine May 1947 ‘What to Make ‘ page.

An unaltered parachute panel where the flawed stitching is clearly visible. Worthing museum.

Parachute silk night dress. Henfield Museum.

Parachute silk night dress. Henfield Museum.

Parachute silk night dress. Henfield Museum.

Parachute silk blouse. Henfield Museum.

Parachute silk blouse. Henfield Museum.

Wedding dress made from curtains, 1940. Henfield Museum.

Wedding dress made from curtains, 1940. Henfield Museum.

Wedding dress made from curtains, 1940. Henfield Museum.

Wedding dress made from curtains, 1940. Henfield Museum.

The wedding outfit may be seen being worn here. Henfield Museum.